The DIB has 99 pages of Butlers. Like the Burkes, an ancient family, Norman, who arrived in the 12th century to conquer, succeeded and multiplied. And like the Burkes, many of them to me are somewhat interchangeable, ruling, fighting and scheming through the centuries with success but without firing the imagination. Then an interesting one pops out of the page. Edmund Butler, archbishop of Cashel from 1524-1551, a schemer with a good helping of Oedipal rage.

His father, Piers Ruadh Butler, 8th earl of Ormond and 1st earl of Ossory was, the DIB will tell us (I'm jumping ahead to page 164), "perhaps the best exemplar of the use of naked ambition and political skill to achieve personal goals in late medieval Ireland." Edmund was Piers' illegitimate son, although he received a papal dispensation declaring him legitimate. He was named by the pope to the archdiocese in 1524, and the appointment was approved by Henry VIII, the English king, who had not yet broken with Rome. But his consecration was delayed, most likely because Edmund had irritated his father by seeking to enforce a disused charter exempting church property from taxation from the feudal lord, a/k/a daddy. Piers needed the money because he was building his military strength to thwart Irish rivals, and took Edmund's tax-dodging very badly. While Piers tried to promote rival candidates for the archbishopric, Edmund began to team up with the very rivals his father was trying to resist. Edmund was not anti-tax: he just wanted the money for himself, and proved ruthless in shaking down the faithful for funds. As the DIB points out, the main reason Piers and Edmund didn't get on was that they were so similar.

As Piers grew in power, the English crown increased its support of Piers as a counterweight: this included giving his archdiocese extra land and brushing aside meritorious accusations of oppression, robbery, and the like. In gratitude, Edmund supported Henry when he split from Rome. As the crown suppressed the monasteries, abbeys and priories, sources of important revenue for Edmund, he was offered very generous land deals to make up the lost income. Once Piers died, Edmund teamed up with the successor, his half-brother James, and was co-opted to make peace with their father's enemies, helping James levy further taxes and giving false evidence against the recalcitrant. He also supported the elevation of Henry VIII from lord to king of Ireland in 1541. After Henry's death, Edward VI attempted to impose outright protestantism on the Irish church, to which Edmund responded first by trying to stay out of the weigh and then by doing what he was asked. Whatever civil wrongs he committed in his life were pardoned in 1550, just before his death.

Eleanor Butler is described by the DIB as "recluse of Llangollen" but that's too weak-watered. She was born in France around 1739 to a Tipperary family that moved back to Ireland. Her father and brother were earls of Ormond, although they do not appear to have used their titles. (The DIB says that the brother, James was the 16th earl: I believe he was the 17th, although I've already made clear my lack of interest in the genealogical punctilios of the peerage.) They were impoverished by the standards of the gentry, and Eleanor (for whatever reason) was not apparently a candidate for marriage. When she was about 29, a 13 year-old girl named Sarah Ponsonby moved to Kilkenny; she and Eleanor formed a close friendship. Both came under pressure from their families: Eleanor was being pushed to enter a convent, while wolves seemed to have circled Sarah. Some time in 1778, Sarah declared that she would "live and die with Miss Butler" and the two attempted to elope, dressed as men: they were caught and sent back. However, at some point, their families appear to have given in and the two set up home in Llangollen in Wales, where they lived out their lives.

The DIB entries on the two women are not exactly congruent. The account of Eleanor, by Frances Clarke, speaks of her, as I mentioned above, as a "recluse" and states that she and Sarah "made a deliberate decision to retire from the world". Sarah's entry, by Noreen Giffney, takes issue with such claims, and a contemporary newspaper report describing the two as "female hermits": she points out that their many visitors included Wordsworth, Coleridge, Edmund Burke, Walter Scott, the Duke of Wellington and Charles Darwin. (Clarke adds Charles' two grandfathers, Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood to the visitors' book: I wonder if they all arrived together?) Clarke and Giffney take quite different tacks as to the nature of their relationship. Clark is noncommittal, citing Eleanor's taking of legal advice (from Edmund Burke) over a newspaper article that implied that their relationship as "unnatural" (Clarke's word, not in quotes). Giffney, more assertive, states that "their lesbianism was not widely recognized", while acknowledging contemporary opinion that went in both directions, one describing them as the most celebrated virgins in Europe and another condemning them as "damned Sapphists" (on reflection, these aren't mutually exclusive). They wore their hair short and "semi-masculine dress". Whatever, they appear to have been prized for their conversation and learning, the Gothic refurbishment of their house and the beautiful gardens that they laid out. Although they rarely left Llangollen, they seemed to know everything that was going on everywhere. Fame may have tarnished them a little: Eleanor was said to be "haughty and imperious" from "incessant homage". They are buried, together with their devoted servant Mary Carryll, in Llangollen church.

I can't remember when I first came across Hubert Butler, but it was some time after his first collection of essays, Escape From The Anthill, appeared in 1985. He was 85, and had been virtually forgotten for more than a generation. The essays, on Ireland, literature and the Balkans, were revelatory, the work of a man raised in Kilkenny where, apart from time at school and university, and extensive travel in Russia, Yugoslavia and Austria, he spent his entire life. A protestant who embraced the independent Irish state, he worked for a while as a librarian, but principally, as the the DIB's entry by Kate Bateman puts it, at "having no career". From the 1940s on, when he inherited the family home at Maidenhall, Co. Kilkenny, he applied himself mainly to writing and travel, and revived the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, which had roots back to the 1840s. After the success of the first book, three more collections of essays appeared: The Children of Drancy and Grandmother and Wolfe Tone, before Butler's death in 1991 and In The Land of Nod, posthumously. They were all extraordinary, an amazing literary output from someone that hardly anybody had previously heard of.

One of the reasons that Butler had been largely forgotten was an incident that occurred in 1952. At the time, much attention was given in Ireland to the plight of faithful catholics in Eastern Europe, particularly in Hungary and Yugoslavia. Public opinion was enlisted by the church and politicians in support of the cause. Butler had no truck with the persecution of catholics by communists. But he knew Yugoslavia very well and spoke fluent Serbo-Croatian. He knew that during the Second World War, elements of the catholic church in Croatia had collaborated with the fascist Ustaše movement in atrocities against, and forced conversions of, the Orthodox population. He publicized this fact, and the fact that some of the very people being lionized in Ireland for their resistance to communism were linked to the crimes perpetrated in Croatia. For this, he was attacked in the press, ostracized and removed from the minor public offices he held. He retreated to Maidenhall, and although he was by no means cut off from the world, he effectively ceased to be a public figure for more than 30 years. Happily, late in life, he was rediscovered and finally enjoyed the approval he always deserved. What made him special? He wrote the truth, elegantly, spinning wise stories often from small local observations. He believed in the richness of an Ireland formed from all of its traditions, including the small southern protestant one to which he belonged. He promoted peace and unity, and damned violence and tyranny. He knew all about the world in which he lived, and described it well, so that we could understand it, too.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

A great doctor, an alpine photographer, two revolutionary consorts, a ravaged painter and a rescued singer

Son of Dracula (1943) is the one where Lon Chaney plays the cunningly-named Alucard, who travels to America. Obviously, nobody was going to work out his true identity from such a sophisticated word-jumble. So, equally clearly, none of you will be able to identify the true location of Lirenda, or its antagonist neighbor Angolea, as depicted in Henry Burkhead's 1646 play A tragedy of Cola's furie, or Lirenda's miserie. In a past life, to which I've previously referred, I spent quite a lot of time in the Bodleian library in Oxford, among whose advantages were holdings comprising virtually every book ever published in English. In my efforts to find something new to say about very well-mined material in 16th and 17th century drama I read some very obscure plays, which would arrive at my desk, dust-encrusted, inspiring science fiction fantasies about 400 year-old plagues preserved in the Bodleian stacks whose spores would be unleashed, fatally, on unsuspecting researchers. Unfortunately, most of these plays did not provide even that distraction: it turned out that they had been rightly consigned to the dust all those years ago, and did not really merit the temporary disinterment that I arranged for them. I suspect that Cola's furie is in that category, although I never got to read it at the time, it having been published six years after the unyielding cut off date for my studies. We don't know much about Henry Burkhead: the DIB thinks he may have been English. But he was somehow connected to the confederation of Kilkenny, which, as I mentioned yesterday, I'm not much interested in writing about. (Two days in a row: how much more uninterested can I be?) In it, the "catholic gentry of Lirenda ... defend their rights against brutal, treacherous Angoleans". That at least, seems to be an illustration of recognizable emotions, similar to those on display in my local pub the other week when Ireland thrashed England at rugby. That Lirendan-Angolean thing is always a rich vein to tap.

Denis Parsons Burkitt was a remarkable scientist. He came from Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, and after studying medicine at Trinity College Dublin he ended up in Africa - he had a parallel interest in missionary work - where he wrote papers on epidemiology and pioneered inexpensive prostheses for amputees. His first major work was on cancer: he first described a form of the disease in African children that came to be known as Burkitt's lymphoma, and his 1958 paper on the subject became a "citation classic", which I understand is a term of art for a widely-cited scientific work. He took a 10,000-mile safari through Africa to identify the coincidence of lymphoma and malaria, which resulted in the first connection between a cancer and a virus. Still working in the challenging conditions of Africa, he also pioneered the use of chemotherapy to treat lymphoma: the DIB says that Burkitt's "work is considered to be one of the most significant contributions to cancer research in the twentieth century."

Upon his return from Africa, he make a second major discovery: the correlation between the lack of dietary fibre and the incidence of colon and rectal cancer: his 1971 paper on the subject is another citation classic. This discovery is cited as the cause of a fundamental change in western diets. He was serious about his christianity and of his own work, he quoted the apostle Paul: "what do you possess that was not given to you? If then you received it as a gift, why take all the credit to yourself"?

It's a bit difficult to keep up with the names of Elizabeth Burnaby. Born Elizabeth Alicia Hawkins-Whitshed, she successively married Gustavus Burnaby, John Frederick Main and Francis Bernard Aubrey Le Blond, taking her husbands' names as appropriate. Since she published photographs, this means her works are listed variously as those of Mrs. Burnaby, Mrs. Main, and Mrs. Le Blond, which can make them difficult to track down. I found a copy of her book High Life and Towers of Silence, in which she's separately described as Mrs Fred. Burnaby and Elizabeth Main. But it's worth persevering because she was truly a remarkable woman, a pioneer of both mountain climbing and photography. She went to the Alps to improve her health, and they clearly had a good effect: she climbed Montblanc and the Matterhorn and many others during a 20-year alpine career, for obvious practical reasons in short skirts. She brought a camera with her from the beginning - first a cumbersome wooden affair with bellows and a tripod, later a smaller roll film camera - and took thousands of photographs, many of which were widely sold and appeared in books: in addition to High Life, she authored Hints on Snow Photography and contributed the photos to E.F. Benson's Winter Sports in Switzerland. (Follow the link to High Life to see some of her pictures.) She was from Greystones in Co. Wicklow, a lovely seaside village, now somewhat suburbanized but still attractive, which I've visited all my life and where my father now lives. The name of her first husband, Burnaby, is prominent in the area: his family had substantial estates there.

Mary and Lizzie Burns, were also impressive women. (Lizzie is in the picture.) Their father emigrated from Ireland to Manchester, and Mary worked as a teenager in the mill owned by the family of the socialist Friedrich Engels. They met in 1842, and she introduced him to the condition of the working class in England - which presumably had some influence on his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1844, which the DIB does not mention. They cohabited without marrying, which somewhat comically earned the disapproval of Karl Marx and his wife Jenny. She took Engels to Ireland in 1856, and he wrote an interesting letter to Marx about their trip. She died suddenly in 1863, around the age of 40: when Engels told Marx, he offered passing sympathy while complaining how short of money he was. Engels then became involved with Lizzie, who had already been living in his and Mary's household. The Marxes seem to have been warmer to her: Eleanor, Karl's daughter, became wedded to Irish nationalism thanks to Lizzie, and they both accompanied Engels on his second visit to Ireland in 1869. They enjoyed themselves, but Engels lamented that the Irish peasant was turning bourgeois. As Lizzie's health began to fail, they moved around England, Scotland and Germany in the hope of her recuperation. The day before her death in 1878, Engels and Lizzie married: she was buried in a catholic cemetery in London: I hope she hadn't turned bourgeois as well.

I'm curious as to why Napoléon Bonaparte was attended by five Irish doctors during his final days in Saint Helena. One of them, Francis Burton, from Tuam, Co. Galway, observed his post mortem and made the mould from which the emperor's death mask was struck - although there was an undignified quarrel over this when a Corsican doctor claimed credit. Burton's nephew was the fascinating and notorious explorer and orientalist Richard Burton.

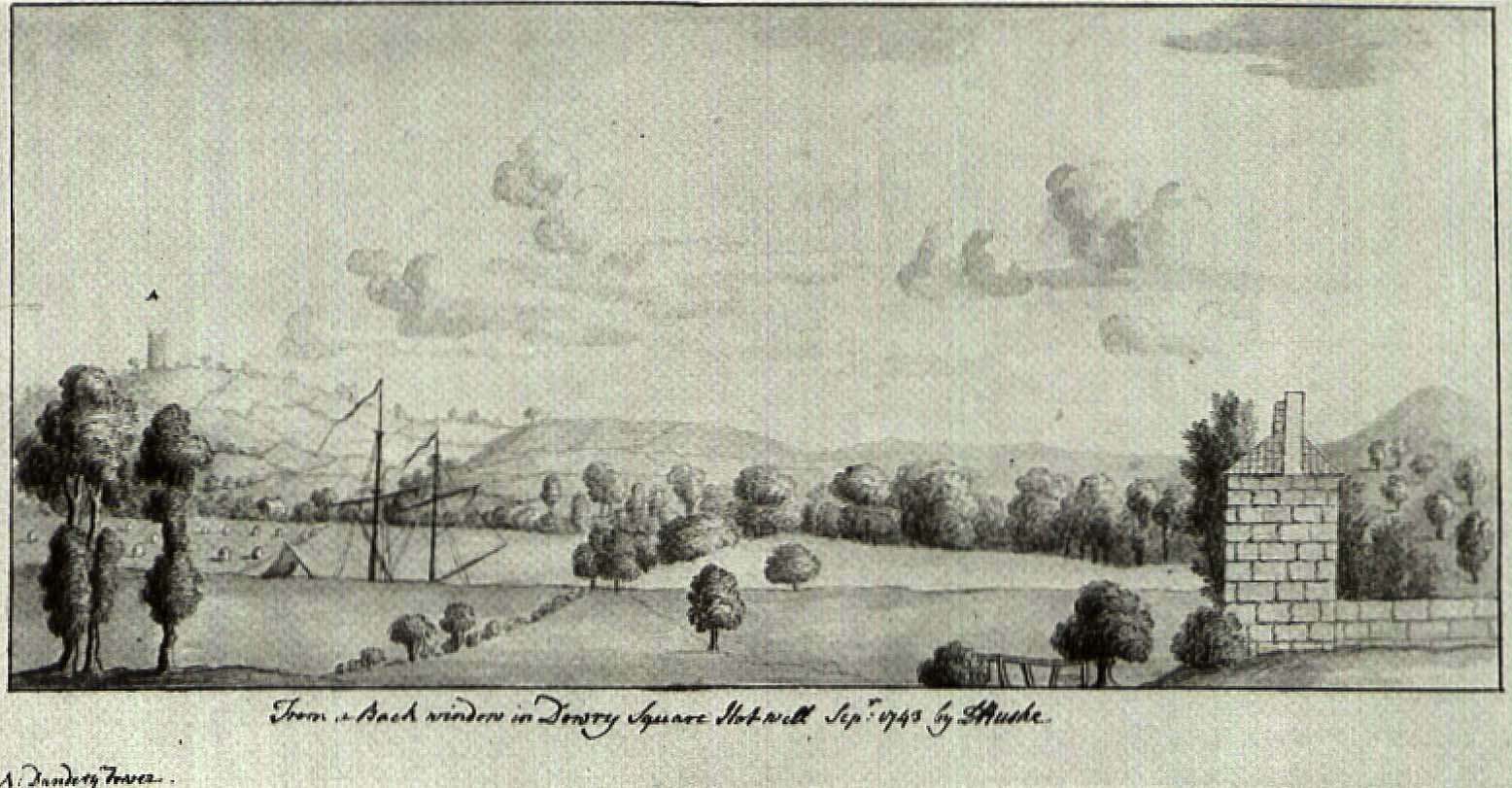

This picture probably does not do justice to the work of the artist Letitia Bushe, a Kilkenny watercolorist and miniaturist. Trinity College Dublin has archived some paintings, but these 18th century public domain works have been locked behind a password-protected wall to which a copyright notice has been attached! For shame ... She was a teacher of many artists, a great conversationalist and a beauty, who was saddened the loss of her former admirers after her looks were ravaged by smallpox.

Eddie Butcher came from a musical family: his father sang, as did nearly all of his siblings. He stayed close to his home in Magilligan, Co. Londonderry, where he worked as a farm laborer and road worker and sang, but never professionally. He had a huge repertoire of folk songs, and fortunately the collector Hugh Shields found him and recorded more than 200 works. He made many more recordings and broadcasts and was greatly appreciated by the 1960s generation of Irish folk singers. I found a recording of a wonderful unaccompanied song, Another Man's Wedding, here. (Legal streaming: do you have a problem with that, Trinity College Dublin?)

Denis Parsons Burkitt was a remarkable scientist. He came from Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh, and after studying medicine at Trinity College Dublin he ended up in Africa - he had a parallel interest in missionary work - where he wrote papers on epidemiology and pioneered inexpensive prostheses for amputees. His first major work was on cancer: he first described a form of the disease in African children that came to be known as Burkitt's lymphoma, and his 1958 paper on the subject became a "citation classic", which I understand is a term of art for a widely-cited scientific work. He took a 10,000-mile safari through Africa to identify the coincidence of lymphoma and malaria, which resulted in the first connection between a cancer and a virus. Still working in the challenging conditions of Africa, he also pioneered the use of chemotherapy to treat lymphoma: the DIB says that Burkitt's "work is considered to be one of the most significant contributions to cancer research in the twentieth century."

Upon his return from Africa, he make a second major discovery: the correlation between the lack of dietary fibre and the incidence of colon and rectal cancer: his 1971 paper on the subject is another citation classic. This discovery is cited as the cause of a fundamental change in western diets. He was serious about his christianity and of his own work, he quoted the apostle Paul: "what do you possess that was not given to you? If then you received it as a gift, why take all the credit to yourself"?

It's a bit difficult to keep up with the names of Elizabeth Burnaby. Born Elizabeth Alicia Hawkins-Whitshed, she successively married Gustavus Burnaby, John Frederick Main and Francis Bernard Aubrey Le Blond, taking her husbands' names as appropriate. Since she published photographs, this means her works are listed variously as those of Mrs. Burnaby, Mrs. Main, and Mrs. Le Blond, which can make them difficult to track down. I found a copy of her book High Life and Towers of Silence, in which she's separately described as Mrs Fred. Burnaby and Elizabeth Main. But it's worth persevering because she was truly a remarkable woman, a pioneer of both mountain climbing and photography. She went to the Alps to improve her health, and they clearly had a good effect: she climbed Montblanc and the Matterhorn and many others during a 20-year alpine career, for obvious practical reasons in short skirts. She brought a camera with her from the beginning - first a cumbersome wooden affair with bellows and a tripod, later a smaller roll film camera - and took thousands of photographs, many of which were widely sold and appeared in books: in addition to High Life, she authored Hints on Snow Photography and contributed the photos to E.F. Benson's Winter Sports in Switzerland. (Follow the link to High Life to see some of her pictures.) She was from Greystones in Co. Wicklow, a lovely seaside village, now somewhat suburbanized but still attractive, which I've visited all my life and where my father now lives. The name of her first husband, Burnaby, is prominent in the area: his family had substantial estates there.

Mary and Lizzie Burns, were also impressive women. (Lizzie is in the picture.) Their father emigrated from Ireland to Manchester, and Mary worked as a teenager in the mill owned by the family of the socialist Friedrich Engels. They met in 1842, and she introduced him to the condition of the working class in England - which presumably had some influence on his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1844, which the DIB does not mention. They cohabited without marrying, which somewhat comically earned the disapproval of Karl Marx and his wife Jenny. She took Engels to Ireland in 1856, and he wrote an interesting letter to Marx about their trip. She died suddenly in 1863, around the age of 40: when Engels told Marx, he offered passing sympathy while complaining how short of money he was. Engels then became involved with Lizzie, who had already been living in his and Mary's household. The Marxes seem to have been warmer to her: Eleanor, Karl's daughter, became wedded to Irish nationalism thanks to Lizzie, and they both accompanied Engels on his second visit to Ireland in 1869. They enjoyed themselves, but Engels lamented that the Irish peasant was turning bourgeois. As Lizzie's health began to fail, they moved around England, Scotland and Germany in the hope of her recuperation. The day before her death in 1878, Engels and Lizzie married: she was buried in a catholic cemetery in London: I hope she hadn't turned bourgeois as well.

I'm curious as to why Napoléon Bonaparte was attended by five Irish doctors during his final days in Saint Helena. One of them, Francis Burton, from Tuam, Co. Galway, observed his post mortem and made the mould from which the emperor's death mask was struck - although there was an undignified quarrel over this when a Corsican doctor claimed credit. Burton's nephew was the fascinating and notorious explorer and orientalist Richard Burton.

This picture probably does not do justice to the work of the artist Letitia Bushe, a Kilkenny watercolorist and miniaturist. Trinity College Dublin has archived some paintings, but these 18th century public domain works have been locked behind a password-protected wall to which a copyright notice has been attached! For shame ... She was a teacher of many artists, a great conversationalist and a beauty, who was saddened the loss of her former admirers after her looks were ravaged by smallpox.

Eddie Butcher came from a musical family: his father sang, as did nearly all of his siblings. He stayed close to his home in Magilligan, Co. Londonderry, where he worked as a farm laborer and road worker and sang, but never professionally. He had a huge repertoire of folk songs, and fortunately the collector Hugh Shields found him and recorded more than 200 works. He made many more recordings and broadcasts and was greatly appreciated by the 1960s generation of Irish folk singers. I found a recording of a wonderful unaccompanied song, Another Man's Wedding, here. (Legal streaming: do you have a problem with that, Trinity College Dublin?)

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

A fenian colonel, a hapless explorer, a bonesetting politician and a pair of serial killers

Ricard (no 'h') O'Sullivan Burke was about 18 when he deserted from the Cork militia - whose name I can never hear without thinking of Percy French's comic song Slattery's Mounted Fut, now somewhat disfavored for its paddywhackery - went to New York, then Central and South America, then California (gold mining), then Chile (joined the cavalry), then back to New York just in time for the civil war. He enlisted in the union army and fought at Bull Run, Yorktown, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg, among other places, and was eventually discharged in 1865 with the rank of brevet colonel, "having gone through the war without a scratch". In his spare time, he organized the Fenian Brotherhood in the Army of the Potomac, preparing himself for peacetime, when he was sent to England to buy guns for the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Like his probably distant relative Thomas Francis Bourke, who fought on the conferederate side, Burke was dispatched to Ireland to provide military experience in the 1867 Fenian uprising. The revolt was something of a fiasco: in Waterford, where Bourke was placed in charge of the Fenian rebels, only around 50 turned out and Bourke sent them home. He went back to England to buy more arms, was arrested and sentenced to 14 years penal servitude. Broken physically and mentally by harsh treatment while incarcerated, he was ultimately released from a prison for the criminally insane in 1871.

Back in the United States, he perked up, wrote patriotic verse, became a well-regarded public speaker, and advised the Fenians on engineering matters, including the extraordinary attempt to finance the building of the submarine designed by John P Holland (more on that when we get to the Hs). He built a railway in Mexico and became assistant city engineer in Omaha, all the while engaged in republican politics - introducing Charles Stewart Parnell to the house of representative and campaigning for James Garfield. What else? When he was 43 he eloped with a 20 year old: he lived to 84.

Many years ago, back in my journalist days, I wrote a magazine feature about a British television series, The Last Place on Earth, written by Trevor Griffiths, about the polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott, based on a book by Roland Huntford. The series caused no end of trouble, principally because it took the view that if everybody on an expedition dies, its leader may be incompetent, not heroic. This seemed to be demonstrably the case given the successes of contemporary polar venturers such as Roald Amundsen and Ernest Shackleton in returning to Europe with their expedition parties largely intact (in Shackleton's case, after masterminding some quite extraordinary rescue and escape plans). All those years later, people seemed to prefer the myth of Scott the doomed hero to Griffiths' depiction of a useless upper class twit (I exaggerate: although that was the gravamen of the case, the portrait was much more nuanced and Scott was finely played by the actor Martin Shaw). All of this came back to me when I was reminded of the Australian equivalent of Scott's expedition: the cross-continental trek of the explorers Robert O'Hara Burke (pictured) and William Wills.

Burke was the Irishman, born in Co. Galway, educated in Belgium and London. He was a Hungarian army officer and an Irish policeman before emigrating to Australia, where he became a well-regarded recruit to the Victoria constabulary. Perhaps because he was liked or politically connected - certainly not for any ability to do the job - he was placed at the head of a trans-continental expedition in 1860. (There were two other Irishmen on the trek, John King and Charles Gray.) Burke made a series of eccentric decisions - dumping some supplies, leaving others behind, walking instead of riding the 25 camels they had brought with them - and fought with other expendition members. After one tiff, Wills was promoted to number two. Nearly six months after setting out from Melbourne, the three Irishmen and Wills reached the northern coast in February 1861. They they tried to go back, with insufficient food. Gray died first, in April. The three others reached their supply post to discover it had been abandoned by other expedition members who had fallen ill and had not received promised resupply. They spent two months reeling around the bush, cadging occasional food from aborigines, who Burke attempted to encourage by firing off gun rounds in their vicinity. He died in June, a day or so after Wills. King, perhaps more prudently, joined an aboriginal group and survived.

Naturally, Burke was proclaimed a hero and given a state funeral and a fine statue in Melbourne. (Irrelevantly, a parliamentary inquiry found that he had acted recklessly.) The DIB places him nicely in two contexts: "his trek forged a myth of heroic failure that has helped shape Australian culture" and "also revealed to more perceptive contemporaries the great skills of aboriginal tribesmen, able to fend for themselves in a landscape that defeated white colonists with every material asset."

As I've mentioned before, I'm skipping interminable Burkes who were earls, lords and baronets, all of whom were unquestionably weighty in their own way, but whose lives somehow merge together in my own insensitive mind. For instance, there was major Burke activity during the Confederation of Kilkenny from 1641-1649, a brief period during which Ireland, or significant parts thereof, freed itself from English rule, before being utterly crushed by Oliver Cromwell. It's an extremely important period of Irish history, characterized by the most byzantine political machinations and of course ending in abject defeat, although not without its moments of glory. I just can't engage with it: I think it's because I made the mistake of flipping the pages to the end of the story, so I know how it turns out. After that, wading through the machinations that lead to the inevitable denouement is just too hard for me. Sorry Burkes, Ormonds, Rinuccinis and others.

Now here's a Burke I can do business with: Thomas Burke, "politician, farmer and bonesetter". He was from Co. Clare, and built his popularity as a setter of broken bones, although the local establishment was less keen on his avocation: one judge chewed out the people of Clare for being too mean to pay for doctors. His paramedical skills propelled him into politics, first as a local councillor, then in the Dáil, where he sat for 14 years. He was dropped from the farmers' party, the Clann na Talmhan, because he refused to pay a levy on his parliamentary salary: in danger of losing his seat, he told Clare voters that he deplored "people so ungrateful as to forget what I have done for them when they were ... only a mere bundle of shattered bones." To send the message home, in the box for party affiliation on the ballot, he inserted the word "Bonesetter". He was re-elected comfortably.

And who wouldn't want to read of William Burke the murderer? Maybe the Burkes work best in pairs, for after Burke and Wills, we have Burke and Hare, the cadaverists. Both were Irish - Burke from Co. Tyrone and William Hare from Newry or Derry - and both ended up in Scotland. The two men and their consorts found themselves in the same boarding house in Edinburgh, run by Mrs. Hare, also from Ulster. Their new business started innocently enough. A lodger died, owing money, and they sold his body to an anatomist, Dr. Robert Knox, for £7 10s. - a lot of money and nearly twice what they were owed. They decided to go into the corpse business, but also to skip the awkward time waiting for people to die, preferring sedation with liquor followed by manual suffocation. In all, they killed 17 people, all of which were sold for good money to a grateful Dr. Knox. Eventually, they were arrested and charged with murder. Hare gave evidence against Burke and managed to escape with the Scottish verdict of "not proven" - not an acquittal but sufficient to secure his release. Burke was hanged in public before a jeering crowd of 20,000. Hare, Mrs. Hare and Burke's lover Helen McDougal all slipped away. When he wasn't practicing mass murder, Burke was apparently "rather jocose and quizzical", "enjoyed music" and "was friendly and affectionate towards local children". That wouldn't include the 12 year old boy he killed for money.

Back in the United States, he perked up, wrote patriotic verse, became a well-regarded public speaker, and advised the Fenians on engineering matters, including the extraordinary attempt to finance the building of the submarine designed by John P Holland (more on that when we get to the Hs). He built a railway in Mexico and became assistant city engineer in Omaha, all the while engaged in republican politics - introducing Charles Stewart Parnell to the house of representative and campaigning for James Garfield. What else? When he was 43 he eloped with a 20 year old: he lived to 84.

Many years ago, back in my journalist days, I wrote a magazine feature about a British television series, The Last Place on Earth, written by Trevor Griffiths, about the polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott, based on a book by Roland Huntford. The series caused no end of trouble, principally because it took the view that if everybody on an expedition dies, its leader may be incompetent, not heroic. This seemed to be demonstrably the case given the successes of contemporary polar venturers such as Roald Amundsen and Ernest Shackleton in returning to Europe with their expedition parties largely intact (in Shackleton's case, after masterminding some quite extraordinary rescue and escape plans). All those years later, people seemed to prefer the myth of Scott the doomed hero to Griffiths' depiction of a useless upper class twit (I exaggerate: although that was the gravamen of the case, the portrait was much more nuanced and Scott was finely played by the actor Martin Shaw). All of this came back to me when I was reminded of the Australian equivalent of Scott's expedition: the cross-continental trek of the explorers Robert O'Hara Burke (pictured) and William Wills.

Burke was the Irishman, born in Co. Galway, educated in Belgium and London. He was a Hungarian army officer and an Irish policeman before emigrating to Australia, where he became a well-regarded recruit to the Victoria constabulary. Perhaps because he was liked or politically connected - certainly not for any ability to do the job - he was placed at the head of a trans-continental expedition in 1860. (There were two other Irishmen on the trek, John King and Charles Gray.) Burke made a series of eccentric decisions - dumping some supplies, leaving others behind, walking instead of riding the 25 camels they had brought with them - and fought with other expendition members. After one tiff, Wills was promoted to number two. Nearly six months after setting out from Melbourne, the three Irishmen and Wills reached the northern coast in February 1861. They they tried to go back, with insufficient food. Gray died first, in April. The three others reached their supply post to discover it had been abandoned by other expedition members who had fallen ill and had not received promised resupply. They spent two months reeling around the bush, cadging occasional food from aborigines, who Burke attempted to encourage by firing off gun rounds in their vicinity. He died in June, a day or so after Wills. King, perhaps more prudently, joined an aboriginal group and survived.

Naturally, Burke was proclaimed a hero and given a state funeral and a fine statue in Melbourne. (Irrelevantly, a parliamentary inquiry found that he had acted recklessly.) The DIB places him nicely in two contexts: "his trek forged a myth of heroic failure that has helped shape Australian culture" and "also revealed to more perceptive contemporaries the great skills of aboriginal tribesmen, able to fend for themselves in a landscape that defeated white colonists with every material asset."

As I've mentioned before, I'm skipping interminable Burkes who were earls, lords and baronets, all of whom were unquestionably weighty in their own way, but whose lives somehow merge together in my own insensitive mind. For instance, there was major Burke activity during the Confederation of Kilkenny from 1641-1649, a brief period during which Ireland, or significant parts thereof, freed itself from English rule, before being utterly crushed by Oliver Cromwell. It's an extremely important period of Irish history, characterized by the most byzantine political machinations and of course ending in abject defeat, although not without its moments of glory. I just can't engage with it: I think it's because I made the mistake of flipping the pages to the end of the story, so I know how it turns out. After that, wading through the machinations that lead to the inevitable denouement is just too hard for me. Sorry Burkes, Ormonds, Rinuccinis and others.

Now here's a Burke I can do business with: Thomas Burke, "politician, farmer and bonesetter". He was from Co. Clare, and built his popularity as a setter of broken bones, although the local establishment was less keen on his avocation: one judge chewed out the people of Clare for being too mean to pay for doctors. His paramedical skills propelled him into politics, first as a local councillor, then in the Dáil, where he sat for 14 years. He was dropped from the farmers' party, the Clann na Talmhan, because he refused to pay a levy on his parliamentary salary: in danger of losing his seat, he told Clare voters that he deplored "people so ungrateful as to forget what I have done for them when they were ... only a mere bundle of shattered bones." To send the message home, in the box for party affiliation on the ballot, he inserted the word "Bonesetter". He was re-elected comfortably.

And who wouldn't want to read of William Burke the murderer? Maybe the Burkes work best in pairs, for after Burke and Wills, we have Burke and Hare, the cadaverists. Both were Irish - Burke from Co. Tyrone and William Hare from Newry or Derry - and both ended up in Scotland. The two men and their consorts found themselves in the same boarding house in Edinburgh, run by Mrs. Hare, also from Ulster. Their new business started innocently enough. A lodger died, owing money, and they sold his body to an anatomist, Dr. Robert Knox, for £7 10s. - a lot of money and nearly twice what they were owed. They decided to go into the corpse business, but also to skip the awkward time waiting for people to die, preferring sedation with liquor followed by manual suffocation. In all, they killed 17 people, all of which were sold for good money to a grateful Dr. Knox. Eventually, they were arrested and charged with murder. Hare gave evidence against Burke and managed to escape with the Scottish verdict of "not proven" - not an acquittal but sufficient to secure his release. Burke was hanged in public before a jeering crowd of 20,000. Hare, Mrs. Hare and Burke's lover Helen McDougal all slipped away. When he wasn't practicing mass murder, Burke was apparently "rather jocose and quizzical", "enjoyed music" and "was friendly and affectionate towards local children". That wouldn't include the 12 year old boy he killed for money.

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Gentleman John's son, the wearer of Miss Daly's dress, a continental painter and the great melodist

You know you're on a journey when you read that the subject was "eldest of the four illegitimate children of Lt-gen. 'Gentleman' John Burgoyne". Gentleman John isn't in the DIB (he's in the Oxford DNB), although his military career took him briefly to Ireland; as a soldier, he is chiefly famous for having commanded the British force that surrendered at Saratoga during the American revolutionary war. He was gentlemanly enough to father his illegitimate children by the same woman, the singer Sarah Caulfield, and to wait until his wife was dead to do so. He was in his 60s, and had switched from the military to a career as a playwright. After his death, his brother-in-law, the Earl of Derby, provided for the upbringing of the four children, including our DIB entry, Sir John Fox Burgoyne, who had a career as a military engineer, based in part in Ireland. (This Derby is the Derby who gave his name to the Derby of horseracing.) Burgoyne was in charge of administering the soup kitchen scheme introduced during the great Irish famine, which briefly provided some form of - barely adequate at best - nutrition for up to three million people but which was swiftly phased out.

Less gentlemanly but perhaps more interesting is John Daly Burk, who crammed a lot into his 36 or so years. He was expelled from Trinity College Dublin for blasphemy (he was a deist) and wrote a defense, The Trial of John Burk (available online for those, not alas including me, who belong to a subscribing library), in which, according to the DIB, he "compared his persecution to that of Priestley, Galileo and Socrates." He moved in radical circles in Dublin, and escaped arrest by decamping from a bookshop surrounded by soldiers in the clothes of a Miss Daly, whence his middle name, adopted in gratitude. (The more I think about that story, the less I believe it). On his way to America, he wrote a play, Bunker Hill, or the Death of General Warren, which according to the DIB was regularly staged on July 4 for over 50 years and made Burk much money, despite bad reviews (one critic appoved only of the fact that it was short). He also wrote an epic on the revolution titles The Columbiad (not to be confused with the Joel Barlow poem of the same title), which remained unpublished ("bombastic and poorly-written", says the DIB), although Burk thought highly enough of it to send extracts to Thomas Jefferson, to whom he later dedicated his History of Virginia. In America, he seems to have been on the better side of most issues: against the alien and sedition acts, anti-slavery, for humane treatment of the Indians, and so on. However, he couldn't prevent himself from living to extremes: he was kicked out of his job as a college principal for adultery, was ordered to leave the United States after being accused of sedition (he didn't, but hid out in Virginia) and finally died in a duel following a row in a tavern: he insulted France, and a Frenchman called him out and shot him.

Augustus Nicholas Burke was a painter from Galway. He was only around 25 when he first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. When he was about 30, he moved to Dublin with his artist sister Dorothy (the subject of this portrait) where he became a successful landscape artist and portraitist. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Irish painters were drawn to the north Atlantic coastline of mainland Europe: Brittany, northern France, Belgium and Holland. Burke was one of the first, and in his later role as professor of painting at the Royal Hibernian Academy, may have encouraged others to do the same. His brother, Thomas Henry Burke, was the leading civil servant in Ireland and was assassinated by a nationalist group, The Invincibles, in Dublin in 1882. Augustus was devastated by his death and left Ireland shortly afterwards, living in London and Italy. He is buried in the English cemetery in Florence. He was a rather fine, if academic and occasionally sentimental painter. A wide selection of his work can be found here.

Edmund Burke is of course one of the truly phenomenal Irish figures of the 18th century, as philosopher, pamphleteer and politician, and accordingly rates a huge entry in the DIB of more than 6 pages, by Eamonn O'Flaherty. I've noticed before that academic historians tend to be rather sniffy about Conor Cruise O'Brien's wonderful portrait of Burke, The Great Melody: it's not mentioned in O'Flaherty's bibliography. O'Brien never wrote anything without an axe to grind, so of course his account is partial, speculative and tendentious. It's also fabulous, including close readings of Burke's writings that are constantly informed by the shrewd intuitions of both the critic and the politician that O'Brien was. (I may say more about O' Brien at some other time - his death was too late to qualify him for the DIB. At this stage, I'll simply say that I'm an admirer, but by no means an unqualified one. I'm fiercely critical of some of his actions in government, as well as some of the political positions he took, particularly in his later life. But I hugely like his book on Burke, warts and all.) W.B. Yeats, in his poem The Seven Sages, had written of the "great melody" of Burke's lengthy and laborious campaigns over America, Ireland, France and India, and O'Brien picked up on the lines to support his conviction of a "profound inner harmony" embracing Burke's approach to these subjects.

O'Brien sees Burke fundamentally as a product of Catholic Ireland, of the Norman gentry that was progressively gaelicized and which by the 18th century, when laws acted as barriers to catholic advancement, was faced with the challenge of how to maintain its declining positions and to compete with the protestant gentry. O'Brien argues that Burke's father, Richard, "conformed" to the established protestant church in order to maintain his practice as a lawyer. (O'Flaherty notes this as merely a possibility, although O'Brien's archival researches on the question seem to have been quite thorough.) His mother, Mary Nagle, remained a catholic, and Burke's early upbringing at home until the age of 11 was, O'Brien believes, in a catholic environment; this ended when he was sent to a quaker school in order, it is argued, to prepare him for entry to the protestant world and the advancement that would be possible for him there. (He also married a catholic.)

One consequence of this experience, according to O'Brien, led Burke to detest the arbitrary exercise of power. This visceral, personal impulse is the strand that ties together his attack on anti-catholic laws in Ireland, his defense of the rights of the American colonists, his onslaught against the excesses and corruption of the East India Company, and his recoil from the violence of the French revolution.

I first encountered Burke at school, where perhaps naturally I was less impressed by his Reflections on the revolution in France, than I was by its riposte, Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man. Temperamentally, as well as politically, I think I still side with Demos against Basileus, but there's no question - and subsequent events everywhere confirm this - that revolt in the name of abstract ideas tends, perhaps inevitably, towards the victimization of thoughtcrime and the institutionalization of new tyranny. Later, as a student, I was very taken with his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, which I was advised to read as an entry-point to the understanding of the gothic in literature and art; shorn of its ultimate grounding in God's providence, its psycho-cultural analysis of the vying influences causing pleasure and fearfulness is an antecedent to Freud's opposition of eros and todestrieb/thanatos. Once one follows O'Brien's fundamentally psychological view of Burke, it is hard not to read into this opposition another key conservative anxiety, at the fissure between culture and anarchy, or between order and oppression.

Thus, Burke saw the enactment of progressive catholic relief laws both as justifiable in itself and as a means of staving off revolutionary elements in Ireland - elements, that of course revolted in 1798. He denounced coercion of American colonists both because it was wrong in itself and would have undesirable political outcomes. He attacked the East India Company (in its day, an even more powerful Halliburton or Blackwater) both because its treatment of India was intrinsically wrong and because its actions injured the British imperial interest in the subcontinent. And his strictures on the French revolution, while foreseeing its descent into tyranny and terror, were also aimed at the geopolitical consequences of so significant an upheaval in a great power.

I think that, ultimately, the reason I can't join the Burke cheering section, at least not wholeheartedly, is because, despite the fact that he about as principled politician as you can get, he was, au fond, a politician. He wanted to preserve the empire and could not comprehend that the very idea was fundamentally despotic. I think that Irish writers such as O'Brien, who quite rightly turned away in horror from the terrible violence of the troubles, wanted to posit an alternative history, whereby Ireland would have evolved painlessly into a modern nation-state, part of the empire/commonwealth, in the same manner as such other white "kith and kin" republics as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Such a view allows for the rejection of the entire "physical force" tradition, dating back at least to 1798, and maybe further. It attacks the undoubtedly self-serving mythologizing that at times evolved into "undisputed historical facts" in recounting elements of the movement for independence. Burke's foresight, intelligence, restraint and conservatism seems superficially to stand against the "bad" Ireland for the "good" (if imagined) one. I'm not so sure. As O'Flaherty points out, in the tense times of the 1790s, when fear of French revolutionary contagion pushed the British government towards repression, Burke supported firm action against domestic radicals and opposed increased toleration of unitarians - laws discriminated against groups that denied the holy trinity in ways similar to discrimination against catholics - suggesting pragmatic limits on his embrace of liberty. He was also strident in his calls for war with France a strategy that arguably led to the domination of Europe by Bonaparte, domination that was only finally undone, after more than 20 years of conflict, by imperial overreaching and then, only thanks to what Burke's fellow Irishman the Duke of Wellington called "the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life", as he described the battle of Waterloo. If you want to get counterfactual, you can enlist Burke for a bad version of history as well as an ideal one.

O'Flaherty concludes of Burke: "Central to all of his concerns was a political theory founded on a combination of pragmatic justice - utilitarian in the tradition of natural law - and a belief in the historical evolution of human society." The first strikes me as inherently suspect: one person's pragmatism is another's self-serving justification. The second is really a fantasy: that the permanent lurches and upheavals of life can be smoothed over by benign forces. The problem with this is that one usually doesn't get to control these forces, and whoever does tends to have motives that are less than benign. So, either as an exemplar of an imagined Ireland, or a founder of certain conservative traditions, these proposed Edmund Burkes don't really persuade me. But he's fascinating and always worth revisiting: one for the ages, if not the pantheon.

Less gentlemanly but perhaps more interesting is John Daly Burk, who crammed a lot into his 36 or so years. He was expelled from Trinity College Dublin for blasphemy (he was a deist) and wrote a defense, The Trial of John Burk (available online for those, not alas including me, who belong to a subscribing library), in which, according to the DIB, he "compared his persecution to that of Priestley, Galileo and Socrates." He moved in radical circles in Dublin, and escaped arrest by decamping from a bookshop surrounded by soldiers in the clothes of a Miss Daly, whence his middle name, adopted in gratitude. (The more I think about that story, the less I believe it). On his way to America, he wrote a play, Bunker Hill, or the Death of General Warren, which according to the DIB was regularly staged on July 4 for over 50 years and made Burk much money, despite bad reviews (one critic appoved only of the fact that it was short). He also wrote an epic on the revolution titles The Columbiad (not to be confused with the Joel Barlow poem of the same title), which remained unpublished ("bombastic and poorly-written", says the DIB), although Burk thought highly enough of it to send extracts to Thomas Jefferson, to whom he later dedicated his History of Virginia. In America, he seems to have been on the better side of most issues: against the alien and sedition acts, anti-slavery, for humane treatment of the Indians, and so on. However, he couldn't prevent himself from living to extremes: he was kicked out of his job as a college principal for adultery, was ordered to leave the United States after being accused of sedition (he didn't, but hid out in Virginia) and finally died in a duel following a row in a tavern: he insulted France, and a Frenchman called him out and shot him.

Augustus Nicholas Burke was a painter from Galway. He was only around 25 when he first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London. When he was about 30, he moved to Dublin with his artist sister Dorothy (the subject of this portrait) where he became a successful landscape artist and portraitist. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Irish painters were drawn to the north Atlantic coastline of mainland Europe: Brittany, northern France, Belgium and Holland. Burke was one of the first, and in his later role as professor of painting at the Royal Hibernian Academy, may have encouraged others to do the same. His brother, Thomas Henry Burke, was the leading civil servant in Ireland and was assassinated by a nationalist group, The Invincibles, in Dublin in 1882. Augustus was devastated by his death and left Ireland shortly afterwards, living in London and Italy. He is buried in the English cemetery in Florence. He was a rather fine, if academic and occasionally sentimental painter. A wide selection of his work can be found here.

Edmund Burke is of course one of the truly phenomenal Irish figures of the 18th century, as philosopher, pamphleteer and politician, and accordingly rates a huge entry in the DIB of more than 6 pages, by Eamonn O'Flaherty. I've noticed before that academic historians tend to be rather sniffy about Conor Cruise O'Brien's wonderful portrait of Burke, The Great Melody: it's not mentioned in O'Flaherty's bibliography. O'Brien never wrote anything without an axe to grind, so of course his account is partial, speculative and tendentious. It's also fabulous, including close readings of Burke's writings that are constantly informed by the shrewd intuitions of both the critic and the politician that O'Brien was. (I may say more about O' Brien at some other time - his death was too late to qualify him for the DIB. At this stage, I'll simply say that I'm an admirer, but by no means an unqualified one. I'm fiercely critical of some of his actions in government, as well as some of the political positions he took, particularly in his later life. But I hugely like his book on Burke, warts and all.) W.B. Yeats, in his poem The Seven Sages, had written of the "great melody" of Burke's lengthy and laborious campaigns over America, Ireland, France and India, and O'Brien picked up on the lines to support his conviction of a "profound inner harmony" embracing Burke's approach to these subjects.

O'Brien sees Burke fundamentally as a product of Catholic Ireland, of the Norman gentry that was progressively gaelicized and which by the 18th century, when laws acted as barriers to catholic advancement, was faced with the challenge of how to maintain its declining positions and to compete with the protestant gentry. O'Brien argues that Burke's father, Richard, "conformed" to the established protestant church in order to maintain his practice as a lawyer. (O'Flaherty notes this as merely a possibility, although O'Brien's archival researches on the question seem to have been quite thorough.) His mother, Mary Nagle, remained a catholic, and Burke's early upbringing at home until the age of 11 was, O'Brien believes, in a catholic environment; this ended when he was sent to a quaker school in order, it is argued, to prepare him for entry to the protestant world and the advancement that would be possible for him there. (He also married a catholic.)

One consequence of this experience, according to O'Brien, led Burke to detest the arbitrary exercise of power. This visceral, personal impulse is the strand that ties together his attack on anti-catholic laws in Ireland, his defense of the rights of the American colonists, his onslaught against the excesses and corruption of the East India Company, and his recoil from the violence of the French revolution.

I first encountered Burke at school, where perhaps naturally I was less impressed by his Reflections on the revolution in France, than I was by its riposte, Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man. Temperamentally, as well as politically, I think I still side with Demos against Basileus, but there's no question - and subsequent events everywhere confirm this - that revolt in the name of abstract ideas tends, perhaps inevitably, towards the victimization of thoughtcrime and the institutionalization of new tyranny. Later, as a student, I was very taken with his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, which I was advised to read as an entry-point to the understanding of the gothic in literature and art; shorn of its ultimate grounding in God's providence, its psycho-cultural analysis of the vying influences causing pleasure and fearfulness is an antecedent to Freud's opposition of eros and todestrieb/thanatos. Once one follows O'Brien's fundamentally psychological view of Burke, it is hard not to read into this opposition another key conservative anxiety, at the fissure between culture and anarchy, or between order and oppression.

Thus, Burke saw the enactment of progressive catholic relief laws both as justifiable in itself and as a means of staving off revolutionary elements in Ireland - elements, that of course revolted in 1798. He denounced coercion of American colonists both because it was wrong in itself and would have undesirable political outcomes. He attacked the East India Company (in its day, an even more powerful Halliburton or Blackwater) both because its treatment of India was intrinsically wrong and because its actions injured the British imperial interest in the subcontinent. And his strictures on the French revolution, while foreseeing its descent into tyranny and terror, were also aimed at the geopolitical consequences of so significant an upheaval in a great power.

I think that, ultimately, the reason I can't join the Burke cheering section, at least not wholeheartedly, is because, despite the fact that he about as principled politician as you can get, he was, au fond, a politician. He wanted to preserve the empire and could not comprehend that the very idea was fundamentally despotic. I think that Irish writers such as O'Brien, who quite rightly turned away in horror from the terrible violence of the troubles, wanted to posit an alternative history, whereby Ireland would have evolved painlessly into a modern nation-state, part of the empire/commonwealth, in the same manner as such other white "kith and kin" republics as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Such a view allows for the rejection of the entire "physical force" tradition, dating back at least to 1798, and maybe further. It attacks the undoubtedly self-serving mythologizing that at times evolved into "undisputed historical facts" in recounting elements of the movement for independence. Burke's foresight, intelligence, restraint and conservatism seems superficially to stand against the "bad" Ireland for the "good" (if imagined) one. I'm not so sure. As O'Flaherty points out, in the tense times of the 1790s, when fear of French revolutionary contagion pushed the British government towards repression, Burke supported firm action against domestic radicals and opposed increased toleration of unitarians - laws discriminated against groups that denied the holy trinity in ways similar to discrimination against catholics - suggesting pragmatic limits on his embrace of liberty. He was also strident in his calls for war with France a strategy that arguably led to the domination of Europe by Bonaparte, domination that was only finally undone, after more than 20 years of conflict, by imperial overreaching and then, only thanks to what Burke's fellow Irishman the Duke of Wellington called "the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life", as he described the battle of Waterloo. If you want to get counterfactual, you can enlist Burke for a bad version of history as well as an ideal one.

O'Flaherty concludes of Burke: "Central to all of his concerns was a political theory founded on a combination of pragmatic justice - utilitarian in the tradition of natural law - and a belief in the historical evolution of human society." The first strikes me as inherently suspect: one person's pragmatism is another's self-serving justification. The second is really a fantasy: that the permanent lurches and upheavals of life can be smoothed over by benign forces. The problem with this is that one usually doesn't get to control these forces, and whoever does tends to have motives that are less than benign. So, either as an exemplar of an imagined Ireland, or a founder of certain conservative traditions, these proposed Edmund Burkes don't really persuade me. But he's fascinating and always worth revisiting: one for the ages, if not the pantheon.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

The source of bunburying, the harp antiquarian, an expensive architect and the first of the De Burghs

Selina Bunbury is one of those writers you've never heard of who turn out to have been quite important in their time. She published more than 100 books. A few have come back into print through public domain publishers and there's been some academic study of her, but I doubt she'll be a big rediscovery. She wrote like this:

By the early part of the 19th century Edward Bunting, from Armagh, was already a prominent musician, church organist, piano teacher and performer. He had become fascinated by the Irish harp through his participation in the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792, whereupon he traveled around Ireland collecting tunes which might otherwise have been on the verge of extinction. He published three collections of the "ancient music of Ireland", all of which are miraculously available, for free, on the internet. He tussled with Thomas Moore over the political significance of traditional Irish music but above all preserved the best for all of us. Derek Bell's recordings of the great blind harpist Turlough Carolan, whose work Bunting notated extensively, are sublime examples. I also found a nice harp version of a Carolan piece here.

And with Edward Bunting, I end the first volume of the DIB. 'Flu has pushed me quite far behind schedule, but it's not as if these lives are going away. I turns out that volume 1, at 989 pages, was just a minnow. Step forward volume 2, a muscular 1148 pages! Much work to be done.

It's not explained in the DIB what "legal reasons" prevented the burial at St. Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork of its architect, William Burges, and I'd really like to know. He won a competition for the commission in 1863; even though the cost of building the cathedral was capped at £15,000: not unusually for major architectural works, the actual building vastly overran its budget, and eventually cost more than £100,000. Burges, who was English and a leader of the gothic revival, sounds like a sympathetic figure: he dressed like a medieval architect, liked pubs that mounted rat hunts (maybe not so sympathetic) and "often greet[ed] his friends with a parrot on either shoulder" (not sure if this means one parrot alternating shoulders or two, split between each shoulder). Even though he didn't get his funeral in Cork, there was a memorial service: according to the DIB, all the church bells were silent on that day.

I imagine that when William de Burgh was en route to Ireland in 1185, bent on conquest and the acquisition of more wealth, at both of which he proved very successful, he little imagined that 800 years later his direct descendant would become famous for composing and performing Patricia the Stripper, surely one of the most dismal attempts at commercial salaciousness of all time. Chris de Burgh isn't in the DIB, although I suppose he will be one day, but there are plenty of William's direct and indirect progeny - de Burghs, de Burgos, Burghs, Burkes and the like - to take us through 74 pages of volume 2. A lot of them were in the conquering and subduing business, and tend to merge together in my mind. But there are some other pleasures to be found, among them Thomas Burgh, a military engineer and architect, who built the magnificent library at Trinity College, one of those sights that all guide books steer you to see but which never disappoints. He also wrote a book on how to measure the areas of rectangles. (I thought you multiplied one side by the other, but it's obviously more complicated than that.)

In the gloomy turret-chamber of a strong tower, near to the coast, lay a wounded English knight who, after having won his spurs by early and valiant service with the noble Sir Philip Sidney, and afterwards with the gallant Essex, was reduced to the sad mortification of having had not only his life endangered, but his good looks, for the time at least, very seriously damaged, by the rude stroke of an Irish club.Much more of that, and you'd want to take a rude stroke of an Irish club to Selina. I only mention her at all because of her surname, and its connection to a bettter Irish writer, Oscar Wilde. In The Importance of Being Earnest, "bunburying" is, of course, the diplomatic excuse for leaving town, on account of the illness or near-death of a friend called Bunbury. While there's a story that the so-called "wickedest man in the world", Aleister Crowley, claimed that Wilde had coined the word through a conflation of the English towns Banbury and Sudbury, it seems far more likely that he was well acquainted with the name, which is not particularly uncommon in Ireland (it has Norman roots). Wilde's fabulous mother Speranza was very well plugged into the Irish literary scene and it seems improbable that Oscar would have been unaware of Selina, or of the mellifluous name on which he conferred immortality.

By the early part of the 19th century Edward Bunting, from Armagh, was already a prominent musician, church organist, piano teacher and performer. He had become fascinated by the Irish harp through his participation in the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792, whereupon he traveled around Ireland collecting tunes which might otherwise have been on the verge of extinction. He published three collections of the "ancient music of Ireland", all of which are miraculously available, for free, on the internet. He tussled with Thomas Moore over the political significance of traditional Irish music but above all preserved the best for all of us. Derek Bell's recordings of the great blind harpist Turlough Carolan, whose work Bunting notated extensively, are sublime examples. I also found a nice harp version of a Carolan piece here.

And with Edward Bunting, I end the first volume of the DIB. 'Flu has pushed me quite far behind schedule, but it's not as if these lives are going away. I turns out that volume 1, at 989 pages, was just a minnow. Step forward volume 2, a muscular 1148 pages! Much work to be done.

It's not explained in the DIB what "legal reasons" prevented the burial at St. Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork of its architect, William Burges, and I'd really like to know. He won a competition for the commission in 1863; even though the cost of building the cathedral was capped at £15,000: not unusually for major architectural works, the actual building vastly overran its budget, and eventually cost more than £100,000. Burges, who was English and a leader of the gothic revival, sounds like a sympathetic figure: he dressed like a medieval architect, liked pubs that mounted rat hunts (maybe not so sympathetic) and "often greet[ed] his friends with a parrot on either shoulder" (not sure if this means one parrot alternating shoulders or two, split between each shoulder). Even though he didn't get his funeral in Cork, there was a memorial service: according to the DIB, all the church bells were silent on that day.

I imagine that when William de Burgh was en route to Ireland in 1185, bent on conquest and the acquisition of more wealth, at both of which he proved very successful, he little imagined that 800 years later his direct descendant would become famous for composing and performing Patricia the Stripper, surely one of the most dismal attempts at commercial salaciousness of all time. Chris de Burgh isn't in the DIB, although I suppose he will be one day, but there are plenty of William's direct and indirect progeny - de Burghs, de Burgos, Burghs, Burkes and the like - to take us through 74 pages of volume 2. A lot of them were in the conquering and subduing business, and tend to merge together in my mind. But there are some other pleasures to be found, among them Thomas Burgh, a military engineer and architect, who built the magnificent library at Trinity College, one of those sights that all guide books steer you to see but which never disappoints. He also wrote a book on how to measure the areas of rectangles. (I thought you multiplied one side by the other, but it's obviously more complicated than that.)

Friday, March 12, 2010

The "moron" bishop, the bishop's antagonist, another botanist and the spycatcher

Michael Browne was catholic bishop of Galway in from 1937 to 1976 and seemed to exemplify everything that was wrong with the church. (I meant to write about him a couple of entries back, but overlooked it: he's accordingly a little out of alphabetical order.) He was among those who led the hierarchy's objections to Noël Browne's mother and child health scheme. He supported a boycott of protestant businesses in Co. Wexford during a dispute over a protestant woman married to a catholic man who refused to educate her children at the local catholic school. He described Trinity College Dublin as "a centre for atheist and communist propaganda". He forced the segregation of the sexes on Galway beaches. He seemed so perpetually angry that his episcopal signature - "† Michael" - was popularly rendered as "Cross Michael". He supervised the construction of a grandiose new cathedral in Galway that local wits dubbed the "Taj Micheáil" (pronounced Meehaul). And it was in connection with the Taj that my life path ever-so-slightly crossed with that of Michael Browne.

In 1966, my father appeared on The Late Late Show, a very long-running Saturday-night TV show that became an outlet for all sorts of discontent in Ireland. My dad contributed to a discussion of popular radio and TV series, one of which he wrote. After he'd left the stage, the real fun began (I was allowed to stay up to watch). A Trinity College undergraduate named Brian Trevaskis said some very rude things about Bishop Browne and his cathedral: one of the words he used was "moron". All hell broke loose - saying even politely critical things about the church was rare in public discourse in those days, and invectve virtually unknown. The papers were full of back and forth for days, and eventually Trevaskis returned to The Late Late Show to apologize. I was allowed to stay up and my memory is that Trevaskis cut a very unimpressive figure to my young eyes and ears - I basically thought he sold out, like Mick Jagger singing "Let's spend some time together" on Ed Sullivan. The record seems to suggest that Trevaskis wasn't as abject as I recall, and that he was quite rude again to Browne.

Of the two, Trevaskis turns out to be the more interesting figure. In 1966, he was quite an old undergraduate (26 or 27) and, contrary to the image of the Trinity student of the time, was both catholic and working class - he had been raised for at least part of his life in an orphanage. He became president of the Trinity debating society, the Phil, and wrote a couple of plays. He also failed his English exams and had to leave. My old undergraduate tutor, Nick Grene, who now has a chair at Trinity and who performed in Trevaskis' plays, kindly provided some memories of him:

I've found that I have a weakness for botanists. Here's another: J.P. Brunker worked for the Guinness brewery and spent weekends in Co. Wicklow, studying the local flora. After 30 years of what the DIB describes as "tramping", he published his master work, The Flora of the County of Wicklow (his DIB entry omits the second "the" and the "of", but I think that may be incorrect). He also contributed to a catalogue of the flora of Co. Dublin. I'd imagined that all of this sort of work had been completed in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it's clear there was still plenty to be done in modern times. Brunker died aged 85 after being injured by a car while conducting field work. I imagine he was descended from Sir Henry Brouncker, an Elizabethan soldier in Ireland I encountered a while back but didn't write about. Sir Henry was so zealous an anti-catholic that even the English privy council told him to tone things down. I'm glad his later relatives were given to gentler pursuits.

For quite a while, we've known about the attempts of German intelligence to place spies in Ireland during the Second World War. There was quite a good miniseries about it in 1984 called Caught in a Free State, which to my recollection depicted the nazi efforts as somewhat hapless, and the attempts of certain IRA elements to engage with them - the usual my-enemy's-enemy-is-my-friend stuff - as close to comical. Hapless, or not, they were spying in a neutral country, and thanks to the Irish intelligence service, G2, headed by Col. Dan Bryan, all 12 nazi spies in Ireland were identified and arrested by the end of 1943. Bryan, with the knowledge of the Irish government, cultivated close relations with British intelligence and exchanged extensive information with it: this did not prevent him from successfully recruiting an informant in the British intelligence operation in Ireland, whose activities he was able to monitor until the end of the war. One of the reasons Bryan was able to roll up the German spy ring was in part because he recruited a librarian-cryptographer, Richard Hayes, who cracked the code they were using. This success was initially withheld from Bryan by subordinates, who believed he would provide the information to MI5. When he got it, he did. Ireland's neutrality caused it serious political and diplomatic problems which the intelligence cooperation was intended to relieve. Unfortunately, even senior figures were unaware of what was happening in the secret world: I've previously written of how Irish diplomacy had to try to overcome the negative impact of the attacks on Irish policy by the wartime U.S. ambassador, David Grey. Bryan's own operation was rolled up at the end of the war, which distressed him no end.

In 1966, my father appeared on The Late Late Show, a very long-running Saturday-night TV show that became an outlet for all sorts of discontent in Ireland. My dad contributed to a discussion of popular radio and TV series, one of which he wrote. After he'd left the stage, the real fun began (I was allowed to stay up to watch). A Trinity College undergraduate named Brian Trevaskis said some very rude things about Bishop Browne and his cathedral: one of the words he used was "moron". All hell broke loose - saying even politely critical things about the church was rare in public discourse in those days, and invectve virtually unknown. The papers were full of back and forth for days, and eventually Trevaskis returned to The Late Late Show to apologize. I was allowed to stay up and my memory is that Trevaskis cut a very unimpressive figure to my young eyes and ears - I basically thought he sold out, like Mick Jagger singing "Let's spend some time together" on Ed Sullivan. The record seems to suggest that Trevaskis wasn't as abject as I recall, and that he was quite rude again to Browne.

Of the two, Trevaskis turns out to be the more interesting figure. In 1966, he was quite an old undergraduate (26 or 27) and, contrary to the image of the Trinity student of the time, was both catholic and working class - he had been raised for at least part of his life in an orphanage. He became president of the Trinity debating society, the Phil, and wrote a couple of plays. He also failed his English exams and had to leave. My old undergraduate tutor, Nick Grene, who now has a chair at Trinity and who performed in Trevaskis' plays, kindly provided some memories of him:

Brian was a quiet spoken, heavy-set man with a red complexion, who was bent on defying all the orthodoxies. He supposedly failed his English exams because he determined to go to the zoo rather than attend the Anglo-Saxon exam, which he regarded as a waste of time; unfortunately he mixed up the timetable and therefore missed another of the literature papers, thereby failing more of the year than was acceptable.In the wake of this setback, he moved to Cornwall (Trevaskis is a Cornish name), joined the church of England, went for a while to Bristol University, and eventually returned to Ireland. He engaged constantly in controversy; attacked, for instance, the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the Easter rising in 1966, the inability of the Irish in Britain to vote in elections back home, the decision of the Abbey Theatre to stage a play by Boucicault that he deemed to be paddywhackery, and dubbing the ruling Fianna Fáil party "neo-fascist". He was hit by a train in north Dublin in 1980, and died. I've read accounts that he committed suicide, but have been unable to confirm these. He seemed to me in the spring of 1966 - I was not yet 9 - to be intelligent, articulate and very angry. As Nick Grene wrote to me: "I was very sad to hear of his later life and death: a waste of energy and talent." Bishop Browne had nothing to do with the death, but he was in a way part of the Ireland that Trevaskis couldn't live with. The old Ireland, I think: it all seems much longer ago.

I've found that I have a weakness for botanists. Here's another: J.P. Brunker worked for the Guinness brewery and spent weekends in Co. Wicklow, studying the local flora. After 30 years of what the DIB describes as "tramping", he published his master work, The Flora of the County of Wicklow (his DIB entry omits the second "the" and the "of", but I think that may be incorrect). He also contributed to a catalogue of the flora of Co. Dublin. I'd imagined that all of this sort of work had been completed in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it's clear there was still plenty to be done in modern times. Brunker died aged 85 after being injured by a car while conducting field work. I imagine he was descended from Sir Henry Brouncker, an Elizabethan soldier in Ireland I encountered a while back but didn't write about. Sir Henry was so zealous an anti-catholic that even the English privy council told him to tone things down. I'm glad his later relatives were given to gentler pursuits.