I was watching the England-Wales rugby march today (it happened yesterday, and I recorded it) and noticed something unusual. It was attended by a British princeling - I think it was the one called Prince William - and whenever Wales scored, he stood up, cheered and applauded. Now, I understand that PW is a patron of the Welsh Rugby Union and that his full title is Prince William of Wales. But I think it goes deeper than this: I'm persuaded that he actually believes he is Welsh. His father, of course, as well as being the Duke of Cornwall, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Chester, Earl of Carrick, Baron Renfrew and Lord of the Isles is the Prince of Wales. But he's not exactly Welsh, really, being of direct descent from a German aristocratic family into which occasional vials of English and Scottish DNA have been mixed. William has a spot of Irish, since his grandmother was a Roche whose people hailed from Cork a while back. But there's very little Welsh in the PW family line, at least not since Henry VII (d. 1509), who was born in Wales of a Welsh family. The Welshness of the Waleses is of quite recent vintage: it was that old Cambrian dog Lloyd George who dreamed up the idea of an investiture ceremony in Caernarfon Castle in 1911 for the future Edward VIII and even taught the young prince a few words of his thrust-upon-him native language. The present occupant of the post went through a similar pageant in 1969, for which he studied somewhat more intensively than his great-uncle. PW is thus only the most recent in an invented tradition of Welshification (or maybe mascotification).

I was thinking about this while reflecting on how people became Irish. The DIB, as we've already seen, is full of various arrivistes. This isn't surprising: Ireland is a small place, close to lots of big places, and you'd expect there to be lots of race-mixing to and fro. In fact, despite continuing self-identity as a highly homogeneous people, the Irish are as mongrelized as any: in my own family tree, other than the Hungarians on my father's side (and leaving aside the Greek gods of which I've previously spoken), I'm aware of Huguenot and Scottish heritage diluting my pure Paddytude, and there are probably other, unknown, miscegenating strains. This is fine by me and completely typical. But at the same time, reading Irish lives makes you very aware of those who elbowed their way in, particularly since so many make the kind of impact that gets them an entry in a dictionary of biography.

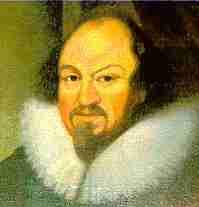

That's Richard Boyle in the picture: the first earl of Cork, who moved from England to Ireland in 1588, when he was about 22. He got himself a really great job: deputy escheator. Escheat is a feudal concept that still exists in common-law jurisdictions: essentially, it means that if the owner of title to land or other property cannot be found, that land or property "escheats" to the feudal lord, or these days to the state. In late 16th century Ireland, there was a lot of escheating going on, as the English crown looked for reasons to confiscate land from the established Ireland. Boyle was very good at this, and found all sorts of reasons to take land away from people who mistakenly believed they owned it. But once confiscated, he then skimmed, building himself a considerable fortune on the side. He then married another fortune, covering up the fact that his wife's late husband had committed suicide, which was another grounds for escheatment to the crown. His wife then obligingly died, leaving him owner of everything. Not unsurprisingly, these activities annoyed people. It was claimed that some Irish rebels took up arms against the English crown because of Boyle's corrupt activities and accordingly he was charged, convicted and jailed. But by this time he had friends in high places: he was released, pardoned, given a new job, fixed up with a second wealthy wife and a deal to buy Sir Walter Raleigh's estates in Cork for a knockdown price - Raleigh apparently needed the money because he was in prison at the time. (We've come across the Raleigh estate once before: the artist Edith Blake lived in his house near Youghal.) Boyle set about building up his fortune again, breaking Raleigh's leases, either to squeeze more money from the tenants or to put in new ones, usually English soldiers and entrepreneurs keen to loot Munster's rich natural resources. Boyle used the money to buy even more estates in Ireland and England; he also obtained the usual titles to go with his wealth and influence - first a knighthood, then a barony and finally an earldom. Hie second wife obliged him with 15 children of which at least 11 seem to have survived to adulthood. Boyle was energetic in obtaining them wealth and preferment, too, building estates and seeking out advantageous marriages. He lived to the age of 74 and died of natural causes. His family motto was "God's providence is my inheritance." I'm not sure what God had to do with it: the substantial inheritance of his family depended in great part on Boyle's dark genius for business, including a filing system that could keep him up to date on his tenants and their payments "at a moment's notice."

His third son, Roger, was similarly gifted. (The heir, also Richard, merely held on during the political upheavals of his lifetime, adding a second earldom and a viscountcy to his tally of titles.) Roger managed to navigate the turbulent politics of early 17th century Ireland with sinewy talent, switching from monarchy to Commonwealth to restored monarchy with great success. His father obtained for him the title Baron Broghill. The elevation to the earldom of Orrery was all his own work: he married the daughter of the earl of Suffolk and rose and rose and rose. Like his father, some of his wealth was obtained corruptly, although maybe not enough: the cost of his lavish lifestyle consistently exceeded his income. His friends praised his "devising head and towering wit". To these virtues the DIB adds "vanity and deviousness". He played the anti-catholic card whenever he had a chance.

The really talented Boyle was the first Richard's 14th child, Robert, who was born in Cork and became one of the outstanding natural philosophers of an outstanding era. He is the Boyle of Boyle's Law - the one about the proportional relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas - who worked tirelessly in experimental science, particularly chemistry and physics, while also seeking to lead an demanding religious life. Michael Hunter of the DIB nicely links the two strands, stating that "his laboratory practice can in many ways be seen as an extension of his indefatigable examination of his conscience."

The professional descriptions of the DIB continue to be illuminating: thus, you have to read the life of Samuel Boyse, once he's presented as "poet, translator and hack writer", and it's well worth it to discover the life of one whose "destitutions and extravagance were considered infamous even by the standards of eighteenth-century literary bohemia. (He once pawned his clothes and his bed linen and sat in bed writing, wrapped in a blanket.) Similarly, it's irresistible to learn about Reginald Brabazon (pictured) once he's been situated as "landowner, philanthropist and disciplinarian." He founded something called the Duty and Discipline Movement (as well as the Lads' Drill Association), whose aims, according to the DIB, were "to combat softness, slackness, indifference, and indiscipline in young people and to give reasonable support to all legitimate authority." Irresistible or not, I think that reading about him is probably preferable to having been in his company.

Finally, Brendan Bracken, a quintessential Mick on the Make, to use Roy Foster's terminology. He left Tipperary at the age of 14, moved to Australia and seems to have spent the rest of his life lying about everything. Less important than the many who disliked and mistrusted him was the small number of influential people - notably, Winston Churchill - who liked him immensely. He ended up a cabinet minister, chairman of the Financial Times and all-round political fixer and charmer, despite an appearance that combined a "mop of read hair and pale freckled skin" with "black teeth". He reaped the usual rewards, including a viscountcy. He downplayed his connections to his father, a monumental sculptor and founder of the Gaelic Athletic Association, as well as all things Irish, although he once produced his birth certificate to refute the claim that he was a Polish jew: in the British society that he embraced there were, after all, some things worse than being Irish. From the non-Welsh Welsh to the non-English English: this identity thing is very complicated.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

The cheating escheator, the physical lawgiver, the strict disciplinarian and the lying climber

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment