At one point, I spent a lot of time sitting in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where I liked to look at girls and occasionally read ancient books. (On one such, an 18th century pamphlet by an Oxford don, a prior reader had written next to the author's name. in impeccable script akin to Bodoni type, "A Dull Rogue!" I felt his pain.) Thomas Bodley was the Merton College fellow who re-organized the library that now bears his name. His youngest brother Josias was also at Merton, but didn't graduate. Instead, he became a soldier, and wound up in Ireland, fighting a further stage of the wars that so benefitted the Blennerhassetts. He was a talented engineer who excelled in the siege of Kinsale on 1601. The book thing seems to have been in the blood, since the conquering army showed its gratitude by subscribing funds to the new library at Trinity College Dublin. Robert also gave the Bod an astronomical quadrant and an armillary sphere (not the one pictured, but like it).

There are quite a number of Bolands in the DIB, so I expected to find something about the greatest of them all, the founder of Boland's Biscuits, still hanging on in Ireland as part of the conglomerated Jacob Fruitfield Group. Boland's Mill in Dublin was also a major site of the Easter Rising, so it wasn't unreasonable to hope for something. Well, I was disappointed. There is a passing reference to Patrick Boland, "a prosperous milling merchant", but none to his biscuit empire that, unlike regular empires, brought peace and pleasure to the people of Ireland. Fortunately, there are other pleasures to be found among the Bolands. John Pius Boland, Patrick's son, won gold medals in the men's single and doubles tennis at the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. He was visiting and was "persuaded to take part". Scandalously, he insisted that the Irish, not the Union flag be raised at the medal ceremonies and the Greeks complied. I'm not sure what Irish flag that would have been - more likely a harp on a Green background or even St Patrick's saltire, not the modern Tricolour. The gesture propelled him into political life, where he served as an Irish party MP at Westminster until 1918.

Most of the other DIB Bolands are a clan that epitomize one historical sweep of Irish life and politics, from fomenting revolution through civil war, the forging of a new state and, ultimately, the discontents of becoming the new political establishment. The story begins with Jim Boland, Manchester-born (in 1856) of parents from Roscommon and Galway. Although he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and was an early leading light of the Gaelic Athletic Association, his activities were as much intra-nationalist as anti-British: he died from head wounds received in a confrontation with other nationalists, reputedly protecting Charles Stewart Parnell.

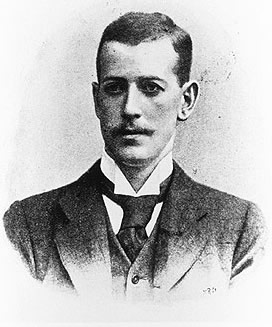

Jim's sons Gerald and Harry (pictured) inherited their father's revolutionary fervor. Gerry was disciplined, sea-green incorruptible: during the war of independence he renounced meat, dairy, alcohol and tobacco, the better to serve the cause. He claimed that his yoga regimen helped him get through the 40-day hunger strike conducteed by anti-treaty prisoners during the civil war. Harry was wilder, a singer, sportsman, drinker and womaniser who rose steadily in republican ranks as he caroused with Michael Collins (they finally fell out, over a woman, Kitty Kiernan, as well as politics). Harry was killed by his former comrades during the civil war, while Gerald survived, perhaps fortunate to have been interned during the worst part of the fighting. Entering politics, he became notorious for cracking down on nationalists who clung to the gun - 15 IRA volunteers died during his time as justice minister - and for instituting censorship during the Second World War, while Ireland was neutral.

Yet he was "a man of comparatively liberal instincts, according to the DIB, for instance pushing back the power of the catholic church despite his personal devoutness. His son Kevin went into the family business, becoming a government minister and interning IRA members. Like his father, he deplored the activities of Taca, which channelled funds from businessmen to his Fianna Fáil party, but unfortunately in his government role he took planning positions similar to that of the Taca beneficiary, Neil Blaney, which led to the destruction of important parts of Dublin's Georgian architecture in the 1960s. (Boland dismissed the conservationists as "belted earls and their ladies and left-wing intellectuals.") On another occasion his red-baiting included an assault on "Conor Cruise Castro God Bless Albania O'Brien." He became isolated in the party as the Troubles progressed, particularly for his attacks on the arms trial. He founded his own completely unsuccessful party (loyally supported by his father, and wrote a number of increasingly blimpish books with title like Fine Gael: British or Irish?) He went on hunger strike against a planning decision (ironic, that). One commentator said that politics was "the last vocation that he should have considered." The DIB tries to be kind, elegantly: Kevin "combined rigid arrogance with a strange innocence; unable to reassess his family's ideological inheritance, he was destroyed by it, raising a limp flag in a sad hour." The problem is that Fianna Fáil, having abandoned anachronistic ideologies, hasn't found a raison d'être to replace them, apart that is from the acquisition and retention of power, at which it continues to excel.

Yet he was "a man of comparatively liberal instincts, according to the DIB, for instance pushing back the power of the catholic church despite his personal devoutness. His son Kevin went into the family business, becoming a government minister and interning IRA members. Like his father, he deplored the activities of Taca, which channelled funds from businessmen to his Fianna Fáil party, but unfortunately in his government role he took planning positions similar to that of the Taca beneficiary, Neil Blaney, which led to the destruction of important parts of Dublin's Georgian architecture in the 1960s. (Boland dismissed the conservationists as "belted earls and their ladies and left-wing intellectuals.") On another occasion his red-baiting included an assault on "Conor Cruise Castro God Bless Albania O'Brien." He became isolated in the party as the Troubles progressed, particularly for his attacks on the arms trial. He founded his own completely unsuccessful party (loyally supported by his father, and wrote a number of increasingly blimpish books with title like Fine Gael: British or Irish?) He went on hunger strike against a planning decision (ironic, that). One commentator said that politics was "the last vocation that he should have considered." The DIB tries to be kind, elegantly: Kevin "combined rigid arrogance with a strange innocence; unable to reassess his family's ideological inheritance, he was destroyed by it, raising a limp flag in a sad hour." The problem is that Fianna Fáil, having abandoned anachronistic ideologies, hasn't found a raison d'être to replace them, apart that is from the acquisition and retention of power, at which it continues to excel.

No comments:

Post a Comment