Anne Bonney is everybody's favorite pirate.(The slovenly-attired doxy in the picture probably looks nothing like the real thing.) You can find a version of her story in Daniel Defoe's A General History of the Pyrates, which includes the observation, based on Bonney's origins and career, that "Bastards have all the Luck." He makes a good point: she was said to have killed her servant with a knife and severely beaten an importuning swain. When she married a loser, her lawyer father, by now translated from Cork to South Carolina, kicked her out of their home and impelled them off to the Bahamas, where she ditched the loser and hooked up with Calico Jack Rackham, the designer of the Jolly Roger. They set off together on a pirate spree: she seems to have embraced the life wholeheartedly, as well as giving birth to one child by Rackham and conceiving another before finally getting caught. Her pregnancy saved her from the rope, and her father pulled strings to get her released, although Rackham was executed. She was only 23. Free of that particular encumbrance, she returned to South Carolina, delivered of Rackham's second child, married again, had eight more children and lived to the age of 84. Luck indeed.

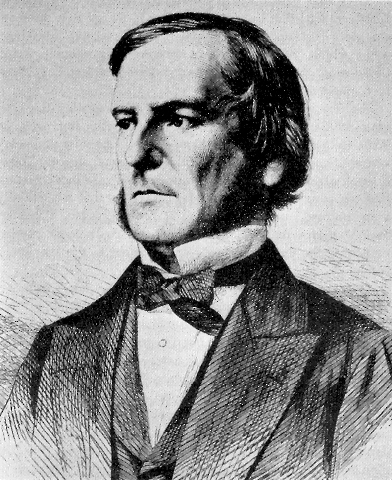

George Boole we know about because of Boolean logic, used by all of us however imperfectly to frame search requests in databases. He was English, from an impoverished family, and basically self-taught; however, he managed to establish connections with leading mathematicians and to publish research papers. When new universities were established in Ireland, Boole was encouraged by the future Lord Kelvin to apply for a chair at Queen's College (now University College), Cork. He had no degree - had not even completed secondary education - but was appointed professor of mathematics in 1849. His work on logic and probability theory was controversial and apparently wrong in many respects - difficult for me, who hasn't tackled a mathematical problem in 35 years and wasn't much good at them back then - to say, although it appears that his approached were influential even if his results were flawed.

George's daughter Alicia, born in Cork, became a distinguished mathematician in her own right (although the DIB refers to her "mathematical hobby"), pioneering research on four-dimensional shapes (she coined the term "polytope", still in use, to describe them). The closest she came to the academy was an honorary degree from Groningen University. Here sister Lucy also never attended university, but became a distinguished chemist: It's reported elsewhere (but not in the DIB) that she became the first woman professor of chemistry at the Royal Free Hospital in London. Another sister, Ethel Voynich, became a successful knowledge The best conclusion to be drawn from the Boole family careers is that a university education should be avoided at all costs.

I discovered a new profession in today's reading: "sailing butler". This title was conferred on one Thomas Kilagallon, who began serving Sir Henry Gore-Booth and his family at the age of 11 and continued for more than 70 years. He became waterborne because Gore-Booth was fond of sailing expeditions, including to the Arctic and he had to accompany his master on these life-threatening voyages. Gore-Booth eventually died of the flu, although only in Switzerland. A scion of a Big House family in Ireland since the 17th century, he had a train named after him following his death. More substantial were Henry's daughters Constance the revolutionary (whom we'll hear more about when we reach her married name, Markievicz) and Eva, described enticingly by the DIB as "poet, mystic, trade unionist and suffragist." (In the picture of the two of them, Eva's on the right.) She campaigned for the rights of the poor, particularly women, including for "pit brow workers, women acrobats, barmaids and Oxford Circus flower sellers." (Explanation: pit brow workers were women who performed manual work above ground at coal mines; Oxford Circus is a busy London intersection, not a circus.) She campaigned, successfully, for her sister's reprieve from execution after the Easter Rising and believed that she remained in post mortem communication with her. After the deaths of Eva and Constance, Yeats, who used to visit their home in his youth, wrote a poem in their memory, Two girls in silk kimonos, both /Beautiful, one a gazelle" (Eva was the gazelle). It's an odd, poignant poem, ambivalent about their political causes but aflame with what they meant, back in those lost days. (An oddity of the DIB: people with double-barrelled names are listed alphabetically by their second such: thus, the Gore-Booths are listed under the "Bs", where I think nobody would go to look for them first.)

I took a shine to Achmet Borumborad, né Patrick Joyce, the "quack and fraud" who promoted Turkish baths in Dublin in the 18th century. He said he was from Constantinople, but probably hailed from Kilkenny. He walked around Dublin in what he said was Turkish dress, including "an immense turban". He was successful in obtaining public financial support for his baths, based on their supposedly health-improving qualities. However, in a hilarious account of a party thrown for Irish parliamentarians, Jonah Barrington describes how the assembled power-brokers became roaring drunk and went tumbling into the baths: Borumborad "espied 18 or 19 Irish Parliament men" in the cold salt-water bath "floating like so many corks upon the surface or scrambling to get out like mice." That was pretty much it for Achmet, although there's a bizarre coda: one William Gregg of Antrim mentioned him in his will, asking that if he should "at any time change his name that he will take the name of William Gregg in remembrance of me." Sometimes, there's so much more you want to know from the shards left to us by these incomplete histories.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Saturday, January 30, 2010

The red rose renter, the librarian soldier, tennis wrapped in the flag and the decline of a dynasty

They must have been ferocious times, those 150 years or so from the mid 16th century on when so much Irish land was confiscated by the British crown (and, for a while, Commonwealth) and reallocated to faithful servants brought in to quell the natives. One thinks of this period in terms of constant violence and upheaval, although there were a few dark jokes along the way. I thought one of those was the grant during the Munster plantation of Gerald FitzGerald's confiscated lands to an English grandee, Thomas Blennerhassett, for a an annual rent of one red rose. At law school you learn about paying rent in peppercorns, so the idea isn't completely alien. That said, it suggests that the spoils came pretty cheap to those who were in the right place at the right time: in fact, it appears not quite as cheap as the DIB has it, since the Blennerhassett family history says he also had to pay six pounds a year. Still, they must have had great laughs every time the red rose thing came up.

At one point, I spent a lot of time sitting in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, where I liked to look at girls and occasionally read ancient books. (On one such, an 18th century pamphlet by an Oxford don, a prior reader had written next to the author's name. in impeccable script akin to Bodoni type, "A Dull Rogue!" I felt his pain.) Thomas Bodley was the Merton College fellow who re-organized the library that now bears his name. His youngest brother Josias was also at Merton, but didn't graduate. Instead, he became a soldier, and wound up in Ireland, fighting a further stage of the wars that so benefitted the Blennerhassetts. He was a talented engineer who excelled in the siege of Kinsale on 1601. The book thing seems to have been in the blood, since the conquering army showed its gratitude by subscribing funds to the new library at Trinity College Dublin. Robert also gave the Bod an astronomical quadrant and an armillary sphere (not the one pictured, but like it).

There are quite a number of Bolands in the DIB, so I expected to find something about the greatest of them all, the founder of Boland's Biscuits, still hanging on in Ireland as part of the conglomerated Jacob Fruitfield Group. Boland's Mill in Dublin was also a major site of the Easter Rising, so it wasn't unreasonable to hope for something. Well, I was disappointed. There is a passing reference to Patrick Boland, "a prosperous milling merchant", but none to his biscuit empire that, unlike regular empires, brought peace and pleasure to the people of Ireland. Fortunately, there are other pleasures to be found among the Bolands. John Pius Boland, Patrick's son, won gold medals in the men's single and doubles tennis at the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. He was visiting and was "persuaded to take part". Scandalously, he insisted that the Irish, not the Union flag be raised at the medal ceremonies and the Greeks complied. I'm not sure what Irish flag that would have been - more likely a harp on a Green background or even St Patrick's saltire, not the modern Tricolour. The gesture propelled him into political life, where he served as an Irish party MP at Westminster until 1918.

Most of the other DIB Bolands are a clan that epitomize one historical sweep of Irish life and politics, from fomenting revolution through civil war, the forging of a new state and, ultimately, the discontents of becoming the new political establishment. The story begins with Jim Boland, Manchester-born (in 1856) of parents from Roscommon and Galway. Although he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and was an early leading light of the Gaelic Athletic Association, his activities were as much intra-nationalist as anti-British: he died from head wounds received in a confrontation with other nationalists, reputedly protecting Charles Stewart Parnell.

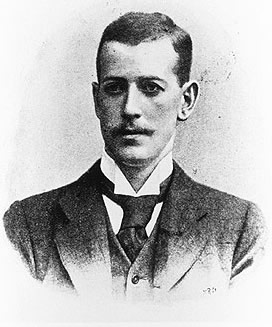

Jim's sons Gerald and Harry (pictured) inherited their father's revolutionary fervor. Gerry was disciplined, sea-green incorruptible: during the war of independence he renounced meat, dairy, alcohol and tobacco, the better to serve the cause. He claimed that his yoga regimen helped him get through the 40-day hunger strike conducteed by anti-treaty prisoners during the civil war. Harry was wilder, a singer, sportsman, drinker and womaniser who rose steadily in republican ranks as he caroused with Michael Collins (they finally fell out, over a woman, Kitty Kiernan, as well as politics). Harry was killed by his former comrades during the civil war, while Gerald survived, perhaps fortunate to have been interned during the worst part of the fighting. Entering politics, he became notorious for cracking down on nationalists who clung to the gun - 15 IRA volunteers died during his time as justice minister - and for instituting censorship during the Second World War, while Ireland was neutral.

Yet he was "a man of comparatively liberal instincts, according to the DIB, for instance pushing back the power of the catholic church despite his personal devoutness. His son Kevin went into the family business, becoming a government minister and interning IRA members. Like his father, he deplored the activities of Taca, which channelled funds from businessmen to his Fianna Fáil party, but unfortunately in his government role he took planning positions similar to that of the Taca beneficiary, Neil Blaney, which led to the destruction of important parts of Dublin's Georgian architecture in the 1960s. (Boland dismissed the conservationists as "belted earls and their ladies and left-wing intellectuals.") On another occasion his red-baiting included an assault on "Conor Cruise Castro God Bless Albania O'Brien." He became isolated in the party as the Troubles progressed, particularly for his attacks on the arms trial. He founded his own completely unsuccessful party (loyally supported by his father, and wrote a number of increasingly blimpish books with title like Fine Gael: British or Irish?) He went on hunger strike against a planning decision (ironic, that). One commentator said that politics was "the last vocation that he should have considered." The DIB tries to be kind, elegantly: Kevin "combined rigid arrogance with a strange innocence; unable to reassess his family's ideological inheritance, he was destroyed by it, raising a limp flag in a sad hour." The problem is that Fianna Fáil, having abandoned anachronistic ideologies, hasn't found a raison d'être to replace them, apart that is from the acquisition and retention of power, at which it continues to excel.

Yet he was "a man of comparatively liberal instincts, according to the DIB, for instance pushing back the power of the catholic church despite his personal devoutness. His son Kevin went into the family business, becoming a government minister and interning IRA members. Like his father, he deplored the activities of Taca, which channelled funds from businessmen to his Fianna Fáil party, but unfortunately in his government role he took planning positions similar to that of the Taca beneficiary, Neil Blaney, which led to the destruction of important parts of Dublin's Georgian architecture in the 1960s. (Boland dismissed the conservationists as "belted earls and their ladies and left-wing intellectuals.") On another occasion his red-baiting included an assault on "Conor Cruise Castro God Bless Albania O'Brien." He became isolated in the party as the Troubles progressed, particularly for his attacks on the arms trial. He founded his own completely unsuccessful party (loyally supported by his father, and wrote a number of increasingly blimpish books with title like Fine Gael: British or Irish?) He went on hunger strike against a planning decision (ironic, that). One commentator said that politics was "the last vocation that he should have considered." The DIB tries to be kind, elegantly: Kevin "combined rigid arrogance with a strange innocence; unable to reassess his family's ideological inheritance, he was destroyed by it, raising a limp flag in a sad hour." The problem is that Fianna Fáil, having abandoned anachronistic ideologies, hasn't found a raison d'être to replace them, apart that is from the acquisition and retention of power, at which it continues to excel.

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

The steeplechaser, the pretend cannibal, the glory-seeking footballer and the glory-seeking politician

I'm not really a believer in foundation stories. It strikes me as unlikely that anybody actually invented the sandwich, let alone the nocturnal gambler, the Earl of that ilk. Years ago, somebody once spun me a story about mayonnaise being named for the Balearic city of Mahón (which may be the case, although the Larousse Gastronomique thinks otherwise), and that Mahón was named for an Irishman named Mahon (it's probably named for a Carthaginian named Mago, as it happens). But the stories stick, like mayonnaise to a spoon, and we seem to like them, if not need them. Mercifully, nobody says the steeplechase is named for Mick Steeple. But it's claimed to be a product of the Irish genius, all the same. In 1752, one Edward Blake raced a Mr. O'Callaghan on horseback from Buttevant church in Co. Cork to the steeple of the church in Doneraile, four and a half miles away. The DIB says that the church is named for St. Leger, but I think it's actually St. Mary's, Viscount St. Leger having built it. One notable feature of the church as pictured: no steeple. Apparently, it blew down in 1825. I'm not sure that I believe that Mr. Blake was responsible for the steeplechase: it seems obvious that people would race towards a well-known place that all knew, and that a village church is an obvious choice. But there's a plaque for Blake and O'Callaghan in Buttevant; who am I to argue with lapidary history?

Colin Blakely, from Bangor, Co. Down, was an actor of the highest order. I was watching him the other night in Billy Wilder's late film, The Private Lives of Sherlock Holmes, in which Blakely played Watson to Robert Stephens' Holmes (and Christopher Lee's Mycroft). It's an uneven film, partly because of studio interference - there are legends about missing footage that are probably, sadly, untrue. But the best parts are wonderful, and one of the very best is the visit of Holmes and Watson to the Russian Ballet, where Watson/Blakely, unleashed by the nearness of so many beautiful women in the corps de ballet, slowly realizes that Holmes, to avoid an unwelcome proposition, has circulated the story that the two of them are a couple. Blakley's performance as the male dancers close in on him, pushing past the gorgeous, disabused, departing danseuses, is a gem of comic rage. I saw him twice in one of his finest stage roles, in a Barry Collins play called Judgement, a three-hour solo piece in which Blakely played a Russian military officer abandoned in a cellar for two months who turns to cannibalism and addresses the audience as his judges. I was about 17 and was so impressed by his performance at the ICA theatre in London that I went to see it again when it transferred to the Old Vic, which was then home to the National Theatre. I used to buy the cheapest tickets back then - I think they were only 40 pence - so found myself down in the front row of the Vic with my friend Neil Haines. Neil was - and is - a wonderful man, but not, shall we say, a lover of heavy theatre. As Blakely worked his way through his - for me - mesemerizing performance (there was no interval) on a bare stage with just one prop, a human bone, Neil fell asleep. (We were in the front row, remember.) After a while, he began to snore. I was mortified, but also in a crisis. If I nudged Neil, I was worried he'd wake with a start, maybe let out a bellow. So I elbowed him gently, disturbing him just enough to stem the noise. I shouldn't have worried. I read that some time later, somebody had a heart attack during a performance. Blakely saw it, jumped off the stage, gave the man CPR, waited for the ambulance to arrive, then climbed back on and resumed his discourse on cannibalism. I'm pretty sure I also saw Blakely play Christ in Dennis Potter's Son of Man on the BBC in 1969, a rough-hewn, demotic Messiah. As I say, he was a wonderful actor.

The least of Danny Blanchflower's achievements was the 10 months he spent managing my team, Chelsea, in 1978-79. It was an abject time for the club, with poor players and no money, and Blanchflower probably did no worse than anybody else would have with the same raw material. His playing career, notably winning the championship and couple double with Tottenham Hotspur in 1961, was just before my time, and distinguished: 56 caps for Northern Ireland, playing in the 1958 World Cup quarter finals, twice footballer of the year. As the DIB puts it, his philosophy was that "football was about glory and that the game should be about beating the other team with style rather than boring them to death." That's still the big issue in Irish football (soccer): how to play well and win? After his playing days, he was a good football journalist, on television and in print. His brother Jackie was also a top-flight player, 12 international caps and one of the legendary Busby Babes of Manchester United that were all but wiped out in the terrible Munich plane crash of 1958 (Jackie received the last rites on the airport runway but survived, his career shattered.)

Our paths have already crossed a couple of times with that of the politican Neil Blaney: his fellow party-member Frank Aiken excoriated the business-friendly cronyism that Blaney championed. And the civil servant Peter Berry blew the whistle on Blaney's efforts to run arms to Northern Ireland in the early years of the Troubles. Blaney was an extraordinary politician, who built a political machine in Donegal - based on that started by his father, Neal - that was so successful that he was able to detach it from his own party and run it independently for several years. Patrick Maume's entry on Blaney in the DIB is quite magisterial - maybe the best I've read so far. His summation is marvellous, writing of "the ruthless authoritarianism which marked his career ... [t]he volatile mixture of calculation, resentment, sophistication, provincialism, ruthlessness, and nostalgia which he displayed is reminiscent of other political figures of his intermediate generation: he might well have become taoiseach but instead became a catalyst for the formation of the Provisional IRA." It convincingly establishes the need for a full biography of Blaney.

Colin Blakely, from Bangor, Co. Down, was an actor of the highest order. I was watching him the other night in Billy Wilder's late film, The Private Lives of Sherlock Holmes, in which Blakely played Watson to Robert Stephens' Holmes (and Christopher Lee's Mycroft). It's an uneven film, partly because of studio interference - there are legends about missing footage that are probably, sadly, untrue. But the best parts are wonderful, and one of the very best is the visit of Holmes and Watson to the Russian Ballet, where Watson/Blakely, unleashed by the nearness of so many beautiful women in the corps de ballet, slowly realizes that Holmes, to avoid an unwelcome proposition, has circulated the story that the two of them are a couple. Blakley's performance as the male dancers close in on him, pushing past the gorgeous, disabused, departing danseuses, is a gem of comic rage. I saw him twice in one of his finest stage roles, in a Barry Collins play called Judgement, a three-hour solo piece in which Blakely played a Russian military officer abandoned in a cellar for two months who turns to cannibalism and addresses the audience as his judges. I was about 17 and was so impressed by his performance at the ICA theatre in London that I went to see it again when it transferred to the Old Vic, which was then home to the National Theatre. I used to buy the cheapest tickets back then - I think they were only 40 pence - so found myself down in the front row of the Vic with my friend Neil Haines. Neil was - and is - a wonderful man, but not, shall we say, a lover of heavy theatre. As Blakely worked his way through his - for me - mesemerizing performance (there was no interval) on a bare stage with just one prop, a human bone, Neil fell asleep. (We were in the front row, remember.) After a while, he began to snore. I was mortified, but also in a crisis. If I nudged Neil, I was worried he'd wake with a start, maybe let out a bellow. So I elbowed him gently, disturbing him just enough to stem the noise. I shouldn't have worried. I read that some time later, somebody had a heart attack during a performance. Blakely saw it, jumped off the stage, gave the man CPR, waited for the ambulance to arrive, then climbed back on and resumed his discourse on cannibalism. I'm pretty sure I also saw Blakely play Christ in Dennis Potter's Son of Man on the BBC in 1969, a rough-hewn, demotic Messiah. As I say, he was a wonderful actor.

The least of Danny Blanchflower's achievements was the 10 months he spent managing my team, Chelsea, in 1978-79. It was an abject time for the club, with poor players and no money, and Blanchflower probably did no worse than anybody else would have with the same raw material. His playing career, notably winning the championship and couple double with Tottenham Hotspur in 1961, was just before my time, and distinguished: 56 caps for Northern Ireland, playing in the 1958 World Cup quarter finals, twice footballer of the year. As the DIB puts it, his philosophy was that "football was about glory and that the game should be about beating the other team with style rather than boring them to death." That's still the big issue in Irish football (soccer): how to play well and win? After his playing days, he was a good football journalist, on television and in print. His brother Jackie was also a top-flight player, 12 international caps and one of the legendary Busby Babes of Manchester United that were all but wiped out in the terrible Munich plane crash of 1958 (Jackie received the last rites on the airport runway but survived, his career shattered.)

Our paths have already crossed a couple of times with that of the politican Neil Blaney: his fellow party-member Frank Aiken excoriated the business-friendly cronyism that Blaney championed. And the civil servant Peter Berry blew the whistle on Blaney's efforts to run arms to Northern Ireland in the early years of the Troubles. Blaney was an extraordinary politician, who built a political machine in Donegal - based on that started by his father, Neal - that was so successful that he was able to detach it from his own party and run it independently for several years. Patrick Maume's entry on Blaney in the DIB is quite magisterial - maybe the best I've read so far. His summation is marvellous, writing of "the ruthless authoritarianism which marked his career ... [t]he volatile mixture of calculation, resentment, sophistication, provincialism, ruthlessness, and nostalgia which he displayed is reminiscent of other political figures of his intermediate generation: he might well have become taoiseach but instead became a catalyst for the formation of the Provisional IRA." It convincingly establishes the need for a full biography of Blaney.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

An inquiring doctor, two fine artists and a classic account of a ravaged Anglo-Irish family

Dorothy Blackham was a Dublin-born artist who exhibited constantly from the 1920s until her death in 1975. She worked on posters, linocuts, book illustrations and paintings, while teaching in Dublin schools. Her principal subjects were Irish landscapes, such as the illustrated Blossoming Chestnuts, first exhibited in Dublin in 1939. I'm descovering so many Irish artists through the DIB, particularly women. I've probably seen Blackham works at some time - they're apparently at the Dublin City Gallery and the Hugh Lane - but they're never previously registered with me. Even reproduced, you can see that she was a very fine artist and her work is worth seeking out, which I will.

Another fine discovery: Edith Blake - Lady Edith to the deferentially inclined - who eloped with her policeman husband and ended up in Canada with him where be was governor of Newfoundland. She had quite outstanding gifts as a scientific illustrator, such as this study of the sphinx moth, made in 1892. She also wrote plays and spoke nine languages. It's claimed that while in the Bahamas, she painted with a pet snake draped around her waist. A large collection of her work is in the Natural History Museum in London; her notebooks are at Myrtle Grove, near Youghal, the 16th century house built by Walter Raleigh in which she died in 1926.

Caroline Blackwood's Irish connections were both thorough and attenuated. Her father was the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, descended from 17th century Scottish planters in Co. Down. Her mother's family were Guinnesses. She was born in London, and raised by nannies on the family estate near Belfast, after which her homes were in England, France and the USA. Instead, and more significantly, she became first muse to others, than a considerable artist in her own right. Her first husband, the painter Lucian Freud, painted her. Her third, the poet Robert Lowell, apostrophized her - "I love you every minute of the day; / you gone is hollow, bored, unbearable" (They divorced and Lowell remarried, but when he died in a New York taxi, he was holding a picture of her, done by Freud.) Lowell's mania distressed and ultimately defeated her, but it was during this marriage that she bloomed as a writer, including of Great Granny Webster, that fantastic account of life in a lunatic Anglo-Irish family. The description of Big House Irish life is marvellous: a ludicrous recreation of the English aristocratic grandeur in a landscape that can't support it, where the roof leaks perpetually and the servants wear wellington boots, where the menus are written in French by Ulster cooks who can't cook and where the narrator's grandfather never reads the Irish papers and refuses to hire catholics. It has something of the English comic gothic of Stella Gibbons and Mervyn Peake. but it depends for much on the madness - sometimes, literal madness - of being transplanted for generations to this unwelcoming place. She describes a ravaged family, and ultimately became ravaged herself although you sense that for her, like the suicidal Aunt Lavinia she describes in Great Granny Webster, that spiritual and emotional extravagance was her way of staving off death, while she could.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

The typographer, the textual scholar, the unlucky Lucans, and the unluckier chief secretary

I have a fondness for typography, which I first learned about in printing classes at school, and then from my father. Michael Biggs was inspired by the great Eric Gill, like him a sculptor and stonecutter as well as typographer. Biggs designed the Irish script typeface for Ireland's pre-Euro banknotes. He carved altars, fonts and other features for churches all over Ireland, including at St Michael's in Dun Laoghaire, whose predecessor was destroyed in 1965 by a huge fire that I remember clearly. In this massive work of so many "great" lives of people who ruled, controlled, killed and otherwise had reign over the lives of others, it's a pleasure to see recorded the contribution of one who wrought many fine ordinary things that form part of our everyday visual furniture. Every time you took out your wallet, you saw something beautiful. The DIB says that Biggs was "a gentle man, affectionate and generous." As George Eliot said, " the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts."

We probably had enough of Charles Bewley yesterday. In between his two ghastly stints in Berlin as a representative of the Irish state, there was a genuinely fine diplomat, Daniel Anthony Binchy, a fluent German speaker who made an impact in the right way - to the extent that any representative of a small country could make an impact in a big one - and received a signed portrait from Hindenberg upon his departure in 1932. He returned to academia, where his was one of the founding appointments of the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies, a distinguished but somewhat eccentrically-constituted institution in that its fields of research are limited to Celtic studies and physics. In the narrow areas of ancient Irish legal history, palaeography and philology, Binchy became a giant. My copy of Fergus Kelly's A Guide to Early Irish Law, published by the DIAS, contains six pages of bibliography; more than one of these consists of works by Binchy. More unhistoric acts.

Another big family: the Binghams. The most famous of these for my generation doesn't figure in the DIB, since other than his family title, the Earldom of Lucan - named for a town west of Dublin - "Lucky" Lord Lucan the nanny-murderer had scant connection to Ireland. Things started well: the first Earl of Lucan, Patrick Sarsfield, was one of the Irish commanders who gave William of Orange's armies a hard time during the 17th century Williamite wars. The title died out, but a distant relative of Sarsfield's arranged for it to be revived in 1776. This new first Earl, Charles, was said to have been regarded with "great respect" by his tenants; this did not protect his home in Castlebar from being ransacked by rebels during the 1798 rising. Otherwise, he was a landed parliamentarian who did his bit for the interests of which he was a part. Sometimes, the details of such people are rather inconsequential: according to the DIB, "he was regarded as an amiable man, respected both in parliament and in Mayo ... [m]usically inclined, he was reasonably proficient on the German flute." Less proficient was the third earl, George (pictured), famous for a historic act: he ordered the catastrophic Charge of Light Brigade at Balaclava during the Crimean War. The DIB tells us that Lucan "lacked all common sense, and his severity and pettiness made him deeply unpopular with his officers and men." Although his military career formally ended then, he continued to accumulate military offices and titles, even being appointed field marshal in his 88th year.

Harold Binks was a Northern Ireland trade union leader. Unusually, he attended a multi-denominational infants school, an experience he later said influenced his anti-sectarianism. He was a classic working-class autodidact who left school at 14, started reading on politics and economics, was drawn into the union movement by both local and global conditions - the Spanish civil war had its impact, as well as poverty in Belfast - and rose and rose. He strove, successfully, to reunite the northern and southern trade union congresses and had his finest hour during the the unionist strike of 1977 which attempted, unsuccessfully, to bring down the Northern Ireland administration. He condemned the strike as a "fascist coup" and tried to mobilize the union movement against it. As so often with historic union moments, his was a gallant failure. But he was not wrong to regard it as "our finest hour."

Augustine Birrell was possibly the most interesting and capable British public servant to rule over the Irish. He was chief secretary in Dublin Castle in the early years of the 20th century and was more sympathetic to Home Rule in particular and catholics in general than most of his predecessors. I've recently been reading Leon Ó Broin's terrific 1966 biography of Birrell, a rich portraint of a genuinely interesting man. In the early part of his tenure, he successfully reorganized the university system and introduced important land reforms. Like many before and after him, he had problems with Irish traditions of political violence. His instinct to avoid coercion - a key element of the policy of his predecessor Balfour - steered him away from confrontation both with Ulster unionists when they began to militarize and the nationalist militias who organized in reponse to them. (Although his confrontation with the union leader Jim Larkin was more typically coercive.) His reputation was largely destroyed when the Easter Rising occurred on his watch: although the intelligence failures before the rising were largely those of other agencies, not of his, he nevertheless took - and accepted - most of the blame. The DIB's entry - by Kevin Barry's grand nephew Eunan O'Halpin - probably strikes the right balance in stating: "Had Birrell retired as he wished in 1913 or 1914, his political obituaries would undoubtedly have been kinder." He strove to do the right thing, which is more than you can say of most of his parliamentary predecessors - and successors in northern Ireland.

One final delight: John Birchenshea, the 17th century musicologist who devised a mathematical system for composition, which he claimed could teach a beginner to compose seven-part harmony in seven months. Deaf people could also learn the system. He helped Samuel Pepys set a couple of poems as songs, and was well paid for it.

We probably had enough of Charles Bewley yesterday. In between his two ghastly stints in Berlin as a representative of the Irish state, there was a genuinely fine diplomat, Daniel Anthony Binchy, a fluent German speaker who made an impact in the right way - to the extent that any representative of a small country could make an impact in a big one - and received a signed portrait from Hindenberg upon his departure in 1932. He returned to academia, where his was one of the founding appointments of the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies, a distinguished but somewhat eccentrically-constituted institution in that its fields of research are limited to Celtic studies and physics. In the narrow areas of ancient Irish legal history, palaeography and philology, Binchy became a giant. My copy of Fergus Kelly's A Guide to Early Irish Law, published by the DIAS, contains six pages of bibliography; more than one of these consists of works by Binchy. More unhistoric acts.

Another big family: the Binghams. The most famous of these for my generation doesn't figure in the DIB, since other than his family title, the Earldom of Lucan - named for a town west of Dublin - "Lucky" Lord Lucan the nanny-murderer had scant connection to Ireland. Things started well: the first Earl of Lucan, Patrick Sarsfield, was one of the Irish commanders who gave William of Orange's armies a hard time during the 17th century Williamite wars. The title died out, but a distant relative of Sarsfield's arranged for it to be revived in 1776. This new first Earl, Charles, was said to have been regarded with "great respect" by his tenants; this did not protect his home in Castlebar from being ransacked by rebels during the 1798 rising. Otherwise, he was a landed parliamentarian who did his bit for the interests of which he was a part. Sometimes, the details of such people are rather inconsequential: according to the DIB, "he was regarded as an amiable man, respected both in parliament and in Mayo ... [m]usically inclined, he was reasonably proficient on the German flute." Less proficient was the third earl, George (pictured), famous for a historic act: he ordered the catastrophic Charge of Light Brigade at Balaclava during the Crimean War. The DIB tells us that Lucan "lacked all common sense, and his severity and pettiness made him deeply unpopular with his officers and men." Although his military career formally ended then, he continued to accumulate military offices and titles, even being appointed field marshal in his 88th year.

Harold Binks was a Northern Ireland trade union leader. Unusually, he attended a multi-denominational infants school, an experience he later said influenced his anti-sectarianism. He was a classic working-class autodidact who left school at 14, started reading on politics and economics, was drawn into the union movement by both local and global conditions - the Spanish civil war had its impact, as well as poverty in Belfast - and rose and rose. He strove, successfully, to reunite the northern and southern trade union congresses and had his finest hour during the the unionist strike of 1977 which attempted, unsuccessfully, to bring down the Northern Ireland administration. He condemned the strike as a "fascist coup" and tried to mobilize the union movement against it. As so often with historic union moments, his was a gallant failure. But he was not wrong to regard it as "our finest hour."

Augustine Birrell was possibly the most interesting and capable British public servant to rule over the Irish. He was chief secretary in Dublin Castle in the early years of the 20th century and was more sympathetic to Home Rule in particular and catholics in general than most of his predecessors. I've recently been reading Leon Ó Broin's terrific 1966 biography of Birrell, a rich portraint of a genuinely interesting man. In the early part of his tenure, he successfully reorganized the university system and introduced important land reforms. Like many before and after him, he had problems with Irish traditions of political violence. His instinct to avoid coercion - a key element of the policy of his predecessor Balfour - steered him away from confrontation both with Ulster unionists when they began to militarize and the nationalist militias who organized in reponse to them. (Although his confrontation with the union leader Jim Larkin was more typically coercive.) His reputation was largely destroyed when the Easter Rising occurred on his watch: although the intelligence failures before the rising were largely those of other agencies, not of his, he nevertheless took - and accepted - most of the blame. The DIB's entry - by Kevin Barry's grand nephew Eunan O'Halpin - probably strikes the right balance in stating: "Had Birrell retired as he wished in 1913 or 1914, his political obituaries would undoubtedly have been kinder." He strove to do the right thing, which is more than you can say of most of his parliamentary predecessors - and successors in northern Ireland.

One final delight: John Birchenshea, the 17th century musicologist who devised a mathematical system for composition, which he claimed could teach a beginner to compose seven-part harmony in seven months. Deaf people could also learn the system. He helped Samuel Pepys set a couple of poems as songs, and was well paid for it.

Friday, January 22, 2010

Harmless drudges, bad and good Bewleys and Billy in the Bowl

I'm sure that many you have been asking, why has nobody previously compiled a dictionary of Irish biography? I'm sure you have. Well, as it happens, they have, and I've been looking at all three of them. They're one volume affairs, each compiled by a single person, which makes them rather impressive. The first, published in 1878, was A Compendium of Irish Biography: Comprising Sketches of Distinguished Irishmen and of Eminent Persons Connected with Ireland by Office or by their Writings, by Alfred John Webb, a nationalist politician. It's a monumental work, with some 1,500 lives over nearly 600 pages, citing 350 authorities as source for the information. The next, published 50 years later in 1928, was A Concise Dictionary of Irish Biography, by John Smyth Crone, a Belfast-born physician who moved to London where he explored his Irish antiquarian interests. Dr. Crone amassed more than 4,000 lives, although in the fewer than 300 pages published, they're capsule entries, albeit useful. Another 50 years on, in 1978, came A Dictionary of Irish Biography, by Henry Boylan, a writer and civil servant, who provided just over 1,000 elegantly-written lives, in under 400 pages. Now comes the DIB, an upstart just 32 years after Boylan's work. It's obviously an enterprise in a different league from its forbears, but also following in their footsteps. All hail these harmless drudges! Enthusiastic amateurs, like myself.

I don't mean to go on about this Irish nazi thing, but there's something about being a "B" that seems to bring it out. I read Charles Bewley's "unreliable" autobiography Memoirs of a Wild Goose a few years back,and while it's full of wit and naughtiness, it can't paper over the deep unpleasantness that lies underneath. He was from an establishment family (of which more later), and he was very bright. He was also a contrarian, so to the consternation of his staunchly unionist and quaker family, he became equally staunchly nationalist and catholic. He was a successful barrister, among other things serving prominently in the courts set up by the Dáil in parallel to the British ones during the war of independence. He was a talented linguist, whose skills included excellent German. Another prominent Sinn Feiner with excellent German was Robert Briscoe, whose Jewish family had moved to Dublin from Lithuania. It was accordingly sensible to send both of them to Germany on an unofficial Irish trade delegation during the war of independence. It did not go well. One night, Bewley turned up drunk at a Berlin cafe and hurled anti-semitic insults at Briscoe and the cafe's Jewish owner. He was thrown out. (Bewley's own account of the incident included the admission that a waiter had asked him if Briscoe was the Irish consul, to which he relied "that he was not, and added that it was not likely that a Jew of this type would be appointed.") He kept it up. When Briscoe attempted to buy a ship for smuggling fugitive IRA men out of Ireland and weapons back in, Bewley told Dublin, falsely, that Briscoe was motivated by financial gain. Bewley tried to obtain premises for the Irish delegation, and told Dublin that he had rejected an offer from a Mr. Loewi and a Mr. Jacobowitz, adding "I think it likely that in any bargain with gentlemen of their ancestry we would not get the best of it." On other occasions, he told Dublin that Briscoe was "out on the make" and "a decidedly ... shady character." To some extent Bewley was pushing at an open door: the minister of external affairs, George Gavan Duffy, to whom he reported, once wrote that Briscoe was "an undesirable person". (Briscoe served for 38 years in the Dáil and became lord mayor of Dublin.)

Worse was to come. After a break, Bewley rejoined the diplomatic service in 1929 and four years later was posted .... back to Berlin. Upon presdenting his credentials to President von Hindenburg he made a point, as the DIB put it, of praising "the rebirth of the German nation under Hitler." He regularly attended nazi rallies, which were avoided by diplomats of other democratic states. Because of his proximity to nazi circles - including Hermann Goering, on whom he later wrote a book that is quoted in Holocaust denial circles - his descriptions of anti-Jewish measures were most thorough and informative. He also added his own spin: that "no Jew is bound by any duty towards a non-Jew", or "bound by the ordinary moral law ... in his relations with non-Jews" and that "the Jew ... strives to destroy [non-Jewish patriotism and religion and morals] when allowed into positions of power or influence." He went on to say that if these precepts were true, it was "only logical for the [German] government to take steps to eliminate an influence ... so fatal to the race." He told a German newspaper in 1937 that "your Reich and its leaders have many admirers among our youth."

One of the the results of the steps that Germany took to "eliminate" this "influence" was that many European Jews became refugees, particularly after the Munich crisis of 1938. Bewley created harrowing scenarios of these Jews turning up on Irish doorsteps, perhaps sneakily slipping first into Britain from which they could easily take the Holyhead ferry to holy Ireland. Dublin accordingly asked Bewley for a report on the state of anti-semitism in Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia - akin to asking Hannibal Lecter for his views on anthropophagy. His report, in the words of the historian Dermot Keogh, "uncritically mirrored the central Nazi ideas on anti-Semitism" and, after lengthy exposition, concluded:

After this, even Dublin had had enough, and Bewley was recalled. Instead, he stayed in continental Europe throughout the Second World War, in Germany and Austria and, having narrowly escaped execution as a collaborator, moved to Rome, where after a period of silence, he was eventually permitted to attend St Patrick's day celebrations at the embassy until his death in 1969. The DIB thinks he desired "to be diametrically different to established conventions and to be awkward." True enough, although supporting the nazis in 1937 Berlin wasn't exactly the sign of a maverick character.

Fortunately, when most Irish, including me, hear the name Bewley, they have much happier associations that the revolting Charles. In particular, they revere Ernest Bewley, a cousin of Charles (they shared a grandfather), who founded the legendary Bewley's Oriental Cafes in Dublin. Bewley's - particularly the remaining branch in Grafton Street (pictured) - has simply been the best place for a cup of tea in everybody's living memory. The flagship Grafton Street branch was in fact the last (1927) of four cafes, the first of which was opened in 1896. Spread over several floors with different rooms of varying function and character, it's a place I still visit whenever I'm in Dublin and eat the cherry buns that my mother introduced me to as a treat on our visits to town. Proust had his madeleine and I (no comparison of literary worth intended) have my Bewley's cherry bun - a vivid taste memory that takes me back to early, fondly-remembered times. To be truthful, the place has had its ups and downs: the cherry buns became heartbreakingly poor in the 1980s (imagine biting into a stale madeleine). Commercial vicissitudes have led to all sorts of transformations and tinkering, not to mention the closure of the Westmoreland St and Great Georges St branches. But on my last visit in 2009 with my mother's sister, it was still as wonderful as ever, and the cherry buns were completely up to scratch. My mother always spoke reverentially of the Bewley family: "quakers" - always a term of approbation with her - and "good to their employees". Ernest's son Victor in particular, who turned around the business and paid off its debts, was always referrred to with great respect.

Some short lives: you'll have gathered by now that the DIB - and I - have something of an antiquarian bent. So it's a pleasant surprise to find a lengthy quote from Shane MacGowan in the middle of an 18th century life. The subject is the Dublin beggar Billy in the Bowl, whose name matched his appearance: he had no legs and moved around in a large bowl with wheels attached. He was apparently a charmer and somewhat successful with women. He was also a robber and ended up in jail, where worthies would come to take a look at him. He's mentioned in Finnegans Wake (the book not the song) and in The Pogues' The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn: the following lines are quoted in full in the DIB: "You remember that foul evening when you heard the banshees howl / There was lazy drunken bastards singing 'Billy in the Bowl' / They took you up to midnight mass and left you in the lurch / So you dropped a button in the plate and spewed up in the church." Fabulous stuff. I haven't been able to find the song MacGowan refers to, although there's a Dubliners' song, The Twang Man, which also mentions it. Charles Bianconi (pictured), an Italian artisan, started a coach service in Tipperary in 1815 with one horse; by the 1840s, he had 100 coaches, 1,400 horses and served 120 cities. Before the railway, it was how you got around Ireland, and even later the Bianconi service remained significant, offering feeder coaches to the main train stations. He embraced nationalist politics and organized monster meetings in Tipperary for Daniel O'Connell; a daughter married the Liberator's nephew and a son his grand-daughter. Isaac Bickerstaff, now all but forgotten, but a formidable dramatist in the 18th century: after a towering 12 years on the London stage, he had to take the conventional route of blackmailed gay men and flee to "the continent", where he died "in poverty and exile" about a century before Oscar Wilde endured a similar fate.

I don't mean to go on about this Irish nazi thing, but there's something about being a "B" that seems to bring it out. I read Charles Bewley's "unreliable" autobiography Memoirs of a Wild Goose a few years back,and while it's full of wit and naughtiness, it can't paper over the deep unpleasantness that lies underneath. He was from an establishment family (of which more later), and he was very bright. He was also a contrarian, so to the consternation of his staunchly unionist and quaker family, he became equally staunchly nationalist and catholic. He was a successful barrister, among other things serving prominently in the courts set up by the Dáil in parallel to the British ones during the war of independence. He was a talented linguist, whose skills included excellent German. Another prominent Sinn Feiner with excellent German was Robert Briscoe, whose Jewish family had moved to Dublin from Lithuania. It was accordingly sensible to send both of them to Germany on an unofficial Irish trade delegation during the war of independence. It did not go well. One night, Bewley turned up drunk at a Berlin cafe and hurled anti-semitic insults at Briscoe and the cafe's Jewish owner. He was thrown out. (Bewley's own account of the incident included the admission that a waiter had asked him if Briscoe was the Irish consul, to which he relied "that he was not, and added that it was not likely that a Jew of this type would be appointed.") He kept it up. When Briscoe attempted to buy a ship for smuggling fugitive IRA men out of Ireland and weapons back in, Bewley told Dublin, falsely, that Briscoe was motivated by financial gain. Bewley tried to obtain premises for the Irish delegation, and told Dublin that he had rejected an offer from a Mr. Loewi and a Mr. Jacobowitz, adding "I think it likely that in any bargain with gentlemen of their ancestry we would not get the best of it." On other occasions, he told Dublin that Briscoe was "out on the make" and "a decidedly ... shady character." To some extent Bewley was pushing at an open door: the minister of external affairs, George Gavan Duffy, to whom he reported, once wrote that Briscoe was "an undesirable person". (Briscoe served for 38 years in the Dáil and became lord mayor of Dublin.)

Worse was to come. After a break, Bewley rejoined the diplomatic service in 1929 and four years later was posted .... back to Berlin. Upon presdenting his credentials to President von Hindenburg he made a point, as the DIB put it, of praising "the rebirth of the German nation under Hitler." He regularly attended nazi rallies, which were avoided by diplomats of other democratic states. Because of his proximity to nazi circles - including Hermann Goering, on whom he later wrote a book that is quoted in Holocaust denial circles - his descriptions of anti-Jewish measures were most thorough and informative. He also added his own spin: that "no Jew is bound by any duty towards a non-Jew", or "bound by the ordinary moral law ... in his relations with non-Jews" and that "the Jew ... strives to destroy [non-Jewish patriotism and religion and morals] when allowed into positions of power or influence." He went on to say that if these precepts were true, it was "only logical for the [German] government to take steps to eliminate an influence ... so fatal to the race." He told a German newspaper in 1937 that "your Reich and its leaders have many admirers among our youth."

One of the the results of the steps that Germany took to "eliminate" this "influence" was that many European Jews became refugees, particularly after the Munich crisis of 1938. Bewley created harrowing scenarios of these Jews turning up on Irish doorsteps, perhaps sneakily slipping first into Britain from which they could easily take the Holyhead ferry to holy Ireland. Dublin accordingly asked Bewley for a report on the state of anti-semitism in Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia - akin to asking Hannibal Lecter for his views on anthropophagy. His report, in the words of the historian Dermot Keogh, "uncritically mirrored the central Nazi ideas on anti-Semitism" and, after lengthy exposition, concluded:

It is ... clear that if the Irish press and public opinion indulge in paroxysms of moral indignation at the teratment of Jews but remain blind and deaf to atrocities committed on Christians in other parts of the world, they lay themsleves open to a charge of ignorance or hypocrisy, and scarcely contribute to an amelioration of the general international situation.

After this, even Dublin had had enough, and Bewley was recalled. Instead, he stayed in continental Europe throughout the Second World War, in Germany and Austria and, having narrowly escaped execution as a collaborator, moved to Rome, where after a period of silence, he was eventually permitted to attend St Patrick's day celebrations at the embassy until his death in 1969. The DIB thinks he desired "to be diametrically different to established conventions and to be awkward." True enough, although supporting the nazis in 1937 Berlin wasn't exactly the sign of a maverick character.

Fortunately, when most Irish, including me, hear the name Bewley, they have much happier associations that the revolting Charles. In particular, they revere Ernest Bewley, a cousin of Charles (they shared a grandfather), who founded the legendary Bewley's Oriental Cafes in Dublin. Bewley's - particularly the remaining branch in Grafton Street (pictured) - has simply been the best place for a cup of tea in everybody's living memory. The flagship Grafton Street branch was in fact the last (1927) of four cafes, the first of which was opened in 1896. Spread over several floors with different rooms of varying function and character, it's a place I still visit whenever I'm in Dublin and eat the cherry buns that my mother introduced me to as a treat on our visits to town. Proust had his madeleine and I (no comparison of literary worth intended) have my Bewley's cherry bun - a vivid taste memory that takes me back to early, fondly-remembered times. To be truthful, the place has had its ups and downs: the cherry buns became heartbreakingly poor in the 1980s (imagine biting into a stale madeleine). Commercial vicissitudes have led to all sorts of transformations and tinkering, not to mention the closure of the Westmoreland St and Great Georges St branches. But on my last visit in 2009 with my mother's sister, it was still as wonderful as ever, and the cherry buns were completely up to scratch. My mother always spoke reverentially of the Bewley family: "quakers" - always a term of approbation with her - and "good to their employees". Ernest's son Victor in particular, who turned around the business and paid off its debts, was always referrred to with great respect.

Some short lives: you'll have gathered by now that the DIB - and I - have something of an antiquarian bent. So it's a pleasant surprise to find a lengthy quote from Shane MacGowan in the middle of an 18th century life. The subject is the Dublin beggar Billy in the Bowl, whose name matched his appearance: he had no legs and moved around in a large bowl with wheels attached. He was apparently a charmer and somewhat successful with women. He was also a robber and ended up in jail, where worthies would come to take a look at him. He's mentioned in Finnegans Wake (the book not the song) and in The Pogues' The Sick Bed of Cuchulainn: the following lines are quoted in full in the DIB: "You remember that foul evening when you heard the banshees howl / There was lazy drunken bastards singing 'Billy in the Bowl' / They took you up to midnight mass and left you in the lurch / So you dropped a button in the plate and spewed up in the church." Fabulous stuff. I haven't been able to find the song MacGowan refers to, although there's a Dubliners' song, The Twang Man, which also mentions it. Charles Bianconi (pictured), an Italian artisan, started a coach service in Tipperary in 1815 with one horse; by the 1840s, he had 100 coaches, 1,400 horses and served 120 cities. Before the railway, it was how you got around Ireland, and even later the Bianconi service remained significant, offering feeder coaches to the main train stations. He embraced nationalist politics and organized monster meetings in Tipperary for Daniel O'Connell; a daughter married the Liberator's nephew and a son his grand-daughter. Isaac Bickerstaff, now all but forgotten, but a formidable dramatist in the 18th century: after a towering 12 years on the London stage, he had to take the conventional route of blackmailed gay men and flee to "the continent", where he died "in poverty and exile" about a century before Oscar Wilde endured a similar fate.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

The tar-water bishop and the go-slow civil servant

I studied law at Berkeley (pronounced Burke-ley), which is named after George, Bishop Berkeley (currently pronounced Barclay). I've long suspected that he pronounced his name the Californian way, based on this circumstantial observation: the pejorative Cockney epithet "berk" (pronounced "burke") is an abbreviation of "Berkshire Hunt" (it rhymes; work it out). It's not pronounced "bark". Anyway ...

Berkeley is called Berkeley because of a poem by Berkeley, called Prospect of Planting Arts and Learning in America, which contains the line "westward the course of empire takes its way." Berkeley, a Kilkenny man, tried to start a university in the Americas - Bermuda was one possible location, Rhode Island another. The venture failed, but the precepts that he expounded influenced the foundation of other new world colleges, including Columbia and Yale. More than 100 years later, when it was planned to locate the new University of California in a dull place near Oakland called Ocean View, one of the trustees, a lawyer named Frederick Billings (the Montana city is named for him), recalled Berkeley's poem, with its appeal to the manifest destiny of the westward push, and suggested the writer's name for the new institution. (The pictured allegorical image, named for the same stanza, is by Emanuel Leutze and hangs in the House of Representatives. Can't get more manifest than that.)

Berkeley, after a career at Trinity College Dublin and his American sojourn, became Bishop of Cloyne in east Cork. It's a small place, not much more than a crossroads, really, with a pub at each corner, close to the more substantial town of Midleton, home to Jameson and Paddy's whiskeys. There's a round tower and the cathedral, St Coleman's, which is more the size of the parish church that it now is. That's about it. When Berkeley moved to Cloyne, in 1734, at the age of 49, he had already had two careers, as an an acclaimed philosopher and, as the DIB puts it, the "social idealist" behind the American university project. He threw himself into his work, particularly into alleviating the poverty of so many within the diocese. While writing theoretically on economics he engaged in practical intervention, encouraging local industry and distributing money to the poor during times of hardship. I own the second edition of his best-seller from this period, Siris: a Chain of Philosophical Reflexions and Inquiries Concerning the Virtues of Tar Water, And divers other Subjects connected together and arising one from another (1744), which bears the epigraph from Galatians, "As we have opportunity, let us do good unto all men." As the DIB explains, Berkeley extolled the virtues of tar water - apparently learned from the Narrangansetts of Rhode Island - as a panacea for a suffering population that otherwise had scant access to medical care: "his claims for the substance were modest; he found it good for alleviating his own health problems, and found that others reported similar results." The wits mocked him, and tar water sales soared. The medicinal use of tar water apparently lasted a long time, although by 1911 the Encyclopedia Britannica would state that "taken in large quantities it causes pain and vomiting and dark urine, symptoms similar to carbolic acid poisoning." Did I mention that Berkeley was a great philosopher? Of course, you knew that already. The DIB's entry, by Paul O'Grady, is both thorough and touching, culminating in a fine tribute from another Irish philosopher, A. A. Luce, "who remarked that one initially thinks on reading him that Berkeley is building a house, but subsequently discovers that he has built a church."

I mentioned a couple of days ago the anti-semitism of "Two-Gun" Pat Belton, the politician and businessman.

Writing the day prior to that about Samuel Beckett, I didn't refer to his role as a witness on behalf of a Jewish cousin ny marriage, Henry Sinclair, who sued the writer Oliver St John Gogarty (of whom more when we get the the Gs), who had written some derogatory and anti-semitic lines which Sinclair claimed, successfully, referred to him. Beckett was roundly blackguarded by Gogarty's barrister, and accused of belonging to a "coterie of bawds and blasphemers". This was in 1937. In 1953, a civil servant at the Department of Justice named Peter Berry responded to a request by Robert Briscoe, a Jewish senior member of the governing party, 1916 combatant and future Lord Mayor of Dublin, that Ireland admit 10 Jewish refugee families from continental Europe. In his memorandum, Berry wrote:

Berry also referred to our old friend "international Jewry" using money to obtain preferential treatment of Jewish refugees. In fact, the cabinet, to which the memorandum was submitted, overruled Berry and decided that 5 of the 10 families should be admitted. Berry - who also owned up to pursuing a "go-slow policy" in dealing with Jewish refugee applications - showed a civil servant mentality typical of his peers in many countries before, during and after the Second World War, including the USA, UK and France. And this unquestionably ugly stuff should not diminish the fact that I'm writing about him today because he ended up a hero in one of the biggest Irish political scandals following independence.

In 1969, when violence in Northern Ireland had reached a very significant and dangerous level, Berry, by then a senior Department of Justice officer, learned that an Irish cabinet minister - later revealed to be Charles Haughey (pictured) - did a deal with the IRA that allowed it to use the Republic of Ireland unmolested for cross-border operations. He also learned that the IRA had been meeting with Captain James Kelly, Ireland's director of military intelligence. Berry later learned that Kelly promised the IRA money to purchase arms, and that Haughey, together with another cabinet member, Neil Blaney, had connived in this scheme, diverting funds from a civilian relief project administered by Haughey. The then-taoiseach (prime minister) Jack Lynch was unaware of this maverick operation by his subordinates. Berry was tipped off that weapons, allegedly acquired by a Flemish ex-nazi restaurateur named Albert Luykx, were due to arrive in Dublin, en route to the North. Berry brought in the police to prevent entry of the weapons and confronted Haughey on the telephone; the shipment was called off. (Ironically, Berry had approved Luykx' admission to Ireland in 1948, during the period he was "going slow" on Jewish applications.) Berry's life was threatened by republicans for his role in the affair, and for testifying against Haughey, Blaney, Kelly and Luykx, among others. The trials, poorly handled by the prosecution, ended in the acquittal of all defendants (or dismissal of charges): Haughey, of course, went on to be taoiseach on two occasions; his utter personal and financial corruption, although widely known, was not officially confirmed until after his retirement.

The DIB's Partrick Maume does a very nice balancing act on Berry, giving space to the significant arguments for both positive and negative assessments. Maume quotes another Irish maverick (and hardly a fan), Noel Browne on Berry: "a main of obsessional type, preoccupied with the minutiae of his job, but a man of extraordinary dedication in his way to what he felt were the best interests of his job." Damned a little with faint praise, but praiseworthy still, up to a point.

Berkeley is called Berkeley because of a poem by Berkeley, called Prospect of Planting Arts and Learning in America, which contains the line "westward the course of empire takes its way." Berkeley, a Kilkenny man, tried to start a university in the Americas - Bermuda was one possible location, Rhode Island another. The venture failed, but the precepts that he expounded influenced the foundation of other new world colleges, including Columbia and Yale. More than 100 years later, when it was planned to locate the new University of California in a dull place near Oakland called Ocean View, one of the trustees, a lawyer named Frederick Billings (the Montana city is named for him), recalled Berkeley's poem, with its appeal to the manifest destiny of the westward push, and suggested the writer's name for the new institution. (The pictured allegorical image, named for the same stanza, is by Emanuel Leutze and hangs in the House of Representatives. Can't get more manifest than that.)

Berkeley, after a career at Trinity College Dublin and his American sojourn, became Bishop of Cloyne in east Cork. It's a small place, not much more than a crossroads, really, with a pub at each corner, close to the more substantial town of Midleton, home to Jameson and Paddy's whiskeys. There's a round tower and the cathedral, St Coleman's, which is more the size of the parish church that it now is. That's about it. When Berkeley moved to Cloyne, in 1734, at the age of 49, he had already had two careers, as an an acclaimed philosopher and, as the DIB puts it, the "social idealist" behind the American university project. He threw himself into his work, particularly into alleviating the poverty of so many within the diocese. While writing theoretically on economics he engaged in practical intervention, encouraging local industry and distributing money to the poor during times of hardship. I own the second edition of his best-seller from this period, Siris: a Chain of Philosophical Reflexions and Inquiries Concerning the Virtues of Tar Water, And divers other Subjects connected together and arising one from another (1744), which bears the epigraph from Galatians, "As we have opportunity, let us do good unto all men." As the DIB explains, Berkeley extolled the virtues of tar water - apparently learned from the Narrangansetts of Rhode Island - as a panacea for a suffering population that otherwise had scant access to medical care: "his claims for the substance were modest; he found it good for alleviating his own health problems, and found that others reported similar results." The wits mocked him, and tar water sales soared. The medicinal use of tar water apparently lasted a long time, although by 1911 the Encyclopedia Britannica would state that "taken in large quantities it causes pain and vomiting and dark urine, symptoms similar to carbolic acid poisoning." Did I mention that Berkeley was a great philosopher? Of course, you knew that already. The DIB's entry, by Paul O'Grady, is both thorough and touching, culminating in a fine tribute from another Irish philosopher, A. A. Luce, "who remarked that one initially thinks on reading him that Berkeley is building a house, but subsequently discovers that he has built a church."

I mentioned a couple of days ago the anti-semitism of "Two-Gun" Pat Belton, the politician and businessman.

Writing the day prior to that about Samuel Beckett, I didn't refer to his role as a witness on behalf of a Jewish cousin ny marriage, Henry Sinclair, who sued the writer Oliver St John Gogarty (of whom more when we get the the Gs), who had written some derogatory and anti-semitic lines which Sinclair claimed, successfully, referred to him. Beckett was roundly blackguarded by Gogarty's barrister, and accused of belonging to a "coterie of bawds and blasphemers". This was in 1937. In 1953, a civil servant at the Department of Justice named Peter Berry responded to a request by Robert Briscoe, a Jewish senior member of the governing party, 1916 combatant and future Lord Mayor of Dublin, that Ireland admit 10 Jewish refugee families from continental Europe. In his memorandum, Berry wrote:

In the administration of the alien laws it has always been recognized ... that the question of admission of aliens of Jewish blood presents a special problem and the alien laws have been administered less liberally in their case ... there is a fairly strong anti-Semitic feeling throughout the country based, perhaps, on historical reasons, the fact that the Jews have remained a separate community within the community and have not permitted themselves to be assimilated, and that for their numbers they appear to have disproportionate wealth and influence. [emphasis added]

In 1969, when violence in Northern Ireland had reached a very significant and dangerous level, Berry, by then a senior Department of Justice officer, learned that an Irish cabinet minister - later revealed to be Charles Haughey (pictured) - did a deal with the IRA that allowed it to use the Republic of Ireland unmolested for cross-border operations. He also learned that the IRA had been meeting with Captain James Kelly, Ireland's director of military intelligence. Berry later learned that Kelly promised the IRA money to purchase arms, and that Haughey, together with another cabinet member, Neil Blaney, had connived in this scheme, diverting funds from a civilian relief project administered by Haughey. The then-taoiseach (prime minister) Jack Lynch was unaware of this maverick operation by his subordinates. Berry was tipped off that weapons, allegedly acquired by a Flemish ex-nazi restaurateur named Albert Luykx, were due to arrive in Dublin, en route to the North. Berry brought in the police to prevent entry of the weapons and confronted Haughey on the telephone; the shipment was called off. (Ironically, Berry had approved Luykx' admission to Ireland in 1948, during the period he was "going slow" on Jewish applications.) Berry's life was threatened by republicans for his role in the affair, and for testifying against Haughey, Blaney, Kelly and Luykx, among others. The trials, poorly handled by the prosecution, ended in the acquittal of all defendants (or dismissal of charges): Haughey, of course, went on to be taoiseach on two occasions; his utter personal and financial corruption, although widely known, was not officially confirmed until after his retirement.

The DIB's Partrick Maume does a very nice balancing act on Berry, giving space to the significant arguments for both positive and negative assessments. Maume quotes another Irish maverick (and hardly a fan), Noel Browne on Berry: "a main of obsessional type, preoccupied with the minutiae of his job, but a man of extraordinary dedication in his way to what he felt were the best interests of his job." Damned a little with faint praise, but praiseworthy still, up to a point.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

The Irish nazi party, the tribune of women workers and assorted lucky colonists

I didn't expect to see these words in the DIB: "... co-founder (1934) of the Irish branch of Hitler's National Socialist Party." I knew that various Germans in high positions in Irish academic and cultural life were nazi sympathizers and worse, but hadn't known that this amounted to a branch. Were there meetings? Membership cards? Agendas, motions moved and seconded, and so on? And what did they talk about? Where Celts fit into racial theory? Which Dublin hotel would be used as Gestapo headquarters? Straight-arm salute techniques? The referenced co-founder will be back again when we get to the "M"s: Adolph Mahr turned up today because, as director of the National Museum, he discouraged a Jewish donor, Albert Bender, from making donations of his father Philip's art collection. However, the correspondence between the two was spread over 7 years and is described as "friendly". Generally, Nazi policy was to "accept" all art "donations" from Jewish clients, so I'm not sure what Mahr's problem was.

Louie Bennett was on one of those activists whose energy leaves you exhausted, just on the page. Starting in the women's suffrage movement, she went on to reorganize a trade union, the Irish Women Workers' Union (IWWU), became a peace campaigner, served in public office and travelled the world in support of a wide range of causes. Partly because of her commitment to non-violence, she kept her distance from the alpha males of the Irish labor movement, notably James Connolly and James Larkin; however, in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, she campaigned against British excesses, speaking against the Black and Tans both in America and to Lloyd George personally. During the Irish civil war, she served on the Women's Peace Committee as a mediator.Protecting the rights of women in the workplace wasn't easy in conservative Ireland: even within the IWWU there was debate in the 1930s over whether it should admit married women with working husbands. She led a successful strike of laundry workers to obtain two weeks' paid holidays and, as the DIB states, "consistently condemned colonialism, fascism and armaments expenditure." I liked this detail of her character: "she often used threatened resignations as a means of controlling her colleagues." Great people aren't always easy to be around.

It's in the nature of colonial matters that dynasties come to dominate. We've seen a few of these families before and the latest are the Beresfords, who carve out 10 pages of the DIB. The first appears to be Tristram Beresford, a Kentish man sent to Ireland to build and fortify Coleraine. He annexed land and looted timber and even the London companies that installed him rebuked his corruption. It was said of him that his "tyrrany in Coleraine equalled that of the Spanish inquisition" but he successfully resisted all efforts to remove him. His son was created a baronet, and his great-great grandson, Marcus, became the Earl of Tyrone. Marcus' son George became Marquess of Waterford. And so on. So entrenched were the Beresfords that Marcus' grandson, also Marcus, was named joint-taster of wines for Dublin port at the age of 9, a position he enjoyed for 24 years (his brother John Claudius succeeded him in this onerous position). I have no idea what this job entailed, but I see from this that in 1734 the job was worth three hundred pounds per year. The Beresfords were politicians, soldiers, churchmen - in other words, enjoying all of the the usual trappings of the entrenched ruling families.I felt a little sorry for George Thomas Beresford, who clearly had no idea of how the tide was turning: He was sent to Eton and rose in the army to the rank of major-general, after which he was installed in various parliamentary seats controlled by his elder brother. He "rarely spoke in parliament, but consistently voted against catholic emancipation" while continuing to accumulate colonial offices: governor of Co. Waterford, colonel of the county militia, and so on. Then - there being 41 catholic voters in his constituency of Waterford for every protestant - in 1825 somebody have the bright idea of fielding a candidate against him (sundy Beresfords had held the seat for 70 years). Of course, he was swept aside - he stood down before the election - although it's unfortunate, if understandable that among his opponents' election slogans was "down with the protestants". He was apparently bitter about the experience, but the family learned something: it changed its mind about catholic emancipation, voted for it, and saw poor George returned unopposed for Waterford in the 1830 election.

The Beresfords still hang on. The Wikipedia entry on the present Marquess of Waterford is so irresistibly ludicrous that it must be quoted in full: